More than 40 years ago, the Illinois legislature sought to reduce the number of defendants in medical malpractice actions by allowing plaintiffs to name health care providers as respondents for the purposes of discovery and convert them to defendants later if the facts showed they were culpable.

State lawmakers did not intend to make it more difficult to bring malpractice actions when they passed section 2-402 of the Code of Civil Procedure in 1976, the Illinois Supreme Court said Thursday.

In a 6-0 decision, the high court reversed rulings by the trial court and Illinois Appellate Court that dismissed a lawsuit filed by Carol Cleeton against Southern Illinois University Healthcare and eight other defendants. They are accused of errors that led to the death of Cleeton’s son.

The law’s purpose was to protect health care providers from excessive litigation, the court said.

“However, there is no indication in the legislative history that the legislators intended to make it more difficult for a plaintiff to name a defendant or convert a respondent in discovery to a defendant,” the opinion says. “The trial court in the case on review misapprehended section 2-402 and its underlying purpose.”

Cleeton’s attorney, Timothy M. Shay, said the Illinois Supreme Court has never before addressed the threshold of evidence required to convert a respondent in a medical malpractice action to a defendant. He said if the decision had gone the other way, plaintiffs’ attorneys would stop naming potential defendants as respondents and instead sue every health care provider who potentially could be liable.

“It would be an absolute mess because of litigation and it wouldn’t benefit doctors because their insurance would have gone up,” Shay said during a telephone interview Thursday.

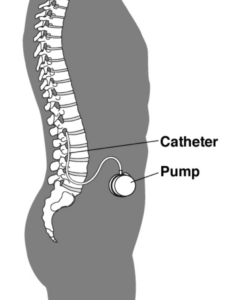

Donald Cleeton severed his spinal cord in swimming pool accident when he was 17 years old, leaving him a quadriplegic. Doctors implanted a device in his body that pumped medicine, called baclofen, into his spinal cavity to control the involuntary spasms caused by nerve damage.

The device required regular refills, which involved inserting a needle through his abdomen. In October 2017, Donald and his mother were visiting the Southern Illinois University neurology clinic to refill the baclofen pump, but two nurses made several failed attempts before finally making contact with the pump and refilling it.

Four days later, Donald was admitted to Memorial Medical Center emergency room complaining of a headache, abdominal pain and increased spasms. The on-call neurology resident recommended that his treating physician have the manufacturer of the baclofen pump, Medtronic, test the pump to see if it was functioning. The test revealed no problems. Treating physicians diagnosed Donald with sepsis and acute urinary tract infection. He was admitted to the hospital.

The next day, Donald was transferred to the hospital’s intensive care unit. The hospital contacted Medtronic for help with troubleshooting the pump. Medtronic faxed instructions to the hospital for emergency procedures to treat baclofen withdrawal syndrome.

Shay said patients who are treated with baclofen cannot suddenly stop using it. Withdrawal from the drug causes symptoms that are similar to sepsis, he said.

A neurologist who examined Donald reported that he may be suffering withdrawal from baclofen, but did not make a firm diagnosis. He discussed the possibility with the ICU physician, Dr. Mouhamad Bakir, but admitted he was not familiar with baclofen withdrwal.

Bakir treated Donald for sepsis. He did not administer baclofen until a “code blue” was called because Donald lost his pulse. By that time, it was too late.

Shay said an autopsy revealed that a catheter connected to the baclofen pump and been punctured, preventing the medicine from reaching Donald’s spinal canal.

Carol Cleeton filed a lawsuit against the hospital, SIU Healthcare and other defendants, but initially Bakir was named only as a respondent because his role in the events that led to Donald’s death were not yet known, Shay said.

When Shay filed a motion to convert Bakir to a defendant, the Sangamom County Circuit Court denied the motion, finding the evidence insufficient. The Appellate Court affirmed the ruling.

The Supreme Court said Section 2-402 requires that a plaintiff demonstrate “probable cause” when requesting to convert a respondent in a medical malpractice suit to a defendant. Both the trial court and Appellate Court, the opinion says, were demanding a higher standard than what the statute requires.

The opinion says Cleeton had presented sufficient evidence to assert that Bakir had deviated from the standard of care by failing to recognize that her son was suffering from baclofen withdrawal syndrome. That isn’t to say that Bakir is liable, the court said, only that Cleeton should have a chance to make her case before a jury.

The opinion says Section 2-402 doesn’t require plaintiffs to prove that a defendant is liable at the discovery stage.

“Instead, the threshold the plaintiff must meet is to present evidence that would establish a reasonable probability that the respondent in discovery could be liable for the plaintiff’s injury,” the opinion says.

The Illinois State Medical Society, American Medical Association, and the Illinois Association of Defense Trial Counsel filed amicus briefs in support of Bakir, but Shay said he believes the Supreme Court’s decision actually benefits doctors.

He said during oral arguments that if the Circuit Court’s decision were not overturned, plaintiffs’ attorneys would return to the “old Wild West days” when every person or institution potentially liable was named as defendants.

The Supreme Court reversed the circuit court and appellate court decisions and remanded the case.

Top photo: Springfield attorney Timothy Shay makes oral arguments before the Illinois Supreme Court in Carol Cleeton’s medical malpractice lawsuit.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud

Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud  Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case  One out of 10 Cars Sold in Europe Is Now Made by a Chinese Brand

One out of 10 Cars Sold in Europe Is Now Made by a Chinese Brand  Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo

Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo