Pinning a dollar value on a bankrupt enterprise is hard in the best of times. During a pandemic, it’s an invitation for a fight.

The Covid-19 outbreak has skewed everything from revenues and expenses to cash flows and net income, making it harder than usual to create a believable model of what a company might be worth. Estimates by bankrupt companies and their bondholders or shareholders differ wildly — half a billion dollars, in one case. This matters for junior creditors, because it determines whether they’ll get some recovery, or perhaps nothing at all, on their busted holdings.

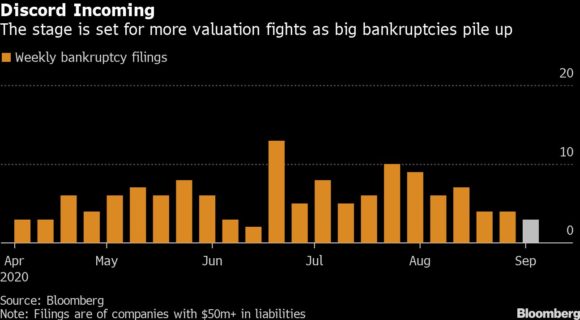

That’s setting off battles among investors, armed with spreadsheets as their weapon of choice. The brawls are playing out in court cases from hospital operators like Quorum Health Corp. to tobacco companies like Pyxus International Inc., and there are likely more on the way.

“Right now we’re in a particularly volatile phase in terms of what value is going to look like,” said Peter Friedman, head of the bankruptcy litigation practice at the law firm O’Melveny & Myers. “There are often huge amounts of money at stake — I would expect parties that can’t consensually resolve outcomes will be ready to litigate valuation.”

“Right now we’re in a particularly volatile phase in terms of what value is going to look like,” said Peter Friedman, head of the bankruptcy litigation practice at the law firm O’Melveny & Myers. “There are often huge amounts of money at stake — I would expect parties that can’t consensually resolve outcomes will be ready to litigate valuation.”

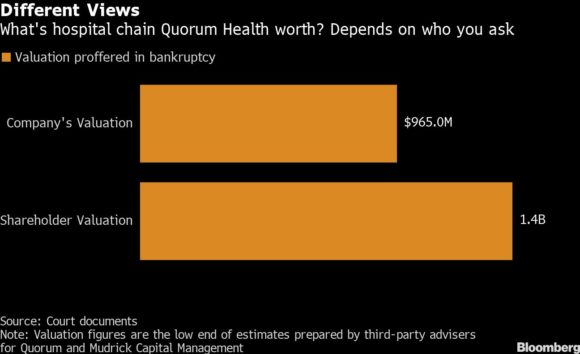

Consider the case of Quorum Health: The rural hospital chain filed for Chapter 11 protection in April as Covid-19 locked down the U.S. economy, but did so with a plan in place to hand ownership to lenders, wipe out existing shareholders and proceed with a much smaller debt load.

Distressed investing veteran Jason Mudrick complicated things. His firm, which owned about 15% of Quorum’s shares, railed against the plan, arguing it was based on a shoddy valuation that ignored hundreds of millions of dollars in federal subsidies. Mudrick enlisted a consultant, Protiviti, that estimated the hospital chain is worth at least $1.4 billion — about $500 million more than Quorum’s estimate of $965 million, court papers show.

The hedge fund’s challenge was overruled in late June, but not before it grilled executives in court, compelled Quorum to turn over loads of company documents and succeeded in delaying its exit from bankruptcy.

“It does seem like an area that gives rise to a lot of cost and time,” said Kenneth Ayotte, a professor of law at UC Berkeley who co-authored a paper on valuation disputes in 2018. “Both sides lose when they have to burn a lot of time and resources on these things.”

Jason Industries Inc., a Wisconsin-based manufacturer of things like lawn mower seats, came face-to-face with that reality last month. The company filed for bankruptcy in June with a plan in place to hand the keys to senior lenders. Its junior lenders, on the other hand, were slated to get almost nothing on their $90 million of debt claims.

Jason Industries Inc., a Wisconsin-based manufacturer of things like lawn mower seats, came face-to-face with that reality last month. The company filed for bankruptcy in June with a plan in place to hand the keys to senior lenders. Its junior lenders, on the other hand, were slated to get almost nothing on their $90 million of debt claims.

Those junior creditors weren’t having it. In the weeks before a federal judge was set to approve Jason’s bankruptcy exit, a group of them accused Jason’s lawyers and bankers of low-balling the valuation, along with other “inappropriate hard-ball tactics.” The creditors argued Jason’s $200 million valuation — prepared by Moelis & Co. — undervalued some of its assets by about $30 million, according to court papers.

The fight went to trial, and after a day of argument and evidence — held virtually, because of the pandemic — the parties settled. The junior lenders got about 5% of the new equity.

Judicial Determinations

“During these volatile times, many parties — especially the ones at the top of the capital stack — are not anxious to seek judicial determinations of value because it is so difficult when you don’t know what the future is going to hold,” said Kevin Carey, a former Delaware bankruptcy judge who is now a partner at Hogan Lovells. Part of the problem is that judges are experts on law, not business valuation. “You listen to the experts, you see if they align on methodology, and you try to pick who has the most credibility,” Carey said.

The other problem for companies, and the reason valuation is such fertile ground for pugnacious investors, is the flimsiness of financial modeling. There’s no universal way to assign a value to a bankrupt company among experts, let alone judges. The options are dizzying: one can try discounting future cash flows, or multiplying previous financial figures, or comparing the company to peers. But then bankers can try to layer in company-specific factors that change the number substantially, something Ayotte argues judges should avoid.

“A skilled valuation expert can get to just about any number that he or she wants,” Ayotte said. “It’s a very strategic game the parties are playing, without a doubt. And the judges are cognizant of that, too.”

–With assistance from Josh Saul.

About the photo: Closed stores and restaurants are seen at Coney Island in the Brooklyn borough of New York, U.S., on Monday, April 20, 2020. Photographer: Holly Pickett/Bloomberg

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud

Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud  One out of 10 Cars Sold in Europe Is Now Made by a Chinese Brand

One out of 10 Cars Sold in Europe Is Now Made by a Chinese Brand  Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says

Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says  Tesla Sued Over Crash That Trapped, Killed Massachusetts Driver

Tesla Sued Over Crash That Trapped, Killed Massachusetts Driver