Wouldn’t it be nice, if, instead of relying on adjusters and restoration companies to surmise how much damage was actually caused by a water leak, an insurer could stop the leak almost before it starts.

That’s now the reality for a growing number of insurers who have deployed leak sensors at commercial, institutional and residential properties. These Internet of Things devices are well on their way to becoming standard features of insurance policies

Chubb, known as the world’s largest publicly traded property insurance company, has embraced the technology wholeheartedly and is pushing ahead with thousands of the hockey-puck-sized sensors around the country. More than 300 Chubb-insured buildings now have the systems in place. It’s all part of Chubb’s declared “war on water damage,” which notes that non-weather-related water damage is one of the biggest drivers of losses for the insurance industry.

Two years into its sensor strategy, the company has compiled a number of examples of how the wireless devices have saved the day and prevented millions of dollars in property losses. In a recent interview with the Insurance Journal, Chubb and an official at Providence College in Rhode Island explained how the devices have worked out.

Providence College has about 4,000 students and 100 acres of grounds and buildings. Shortly after the COVID-19 pandemic hit, though, most students, faculty and staff were working at home. That’s when a washing machine supply line on an upper floor of a residence hall began leaking one night.

And no one was there to see the drip, said Andy Sullivan, assistant vice president for physical plant at the college

If the leak had persisted for hours, it likely would have damaged nearby dorm rooms, elevator components and sensitive and expensive electrical and computer network panels.

“The potential damage could have been significant, maybe hundreds of thousands, depending on when we would have discovered it,” Sullivan said.

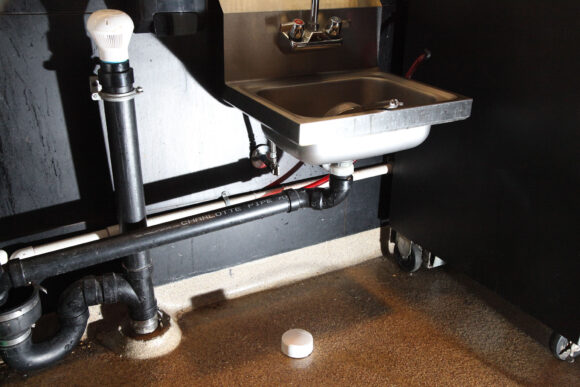

Fortunately for Providence and for Chubb, its primary insurer, the college had just a few weeks earlier installed the wireless leak detectors at strategic sites around the campus. With a text, email, then a phone call from a service center that pinpointed the leak, a worker was able to respond quickly and shut the pipe off.

The laundry room sensor is one of 180 leak detectors and 20 temperature sensors Providence had installed. If someone leaves a door open, a sensor will alert maintenance personnel when the temperature approaches freezing, potential averting frozen and burst pipes.

The cost to Providence is about $12,000 per year, or roughly $600 to $700 per building. In return, Chubb gives the institution a credit on its annual insurance premiums.

“There is the cost of the sensors and the hub connection, but we believe one loss prevention will pay for itself,” said Hemant Sarma, senior vice president and head of Internet of Things for Chubb. “It’s what we call ‘making invisible risk actionable.'”

Sarma calls this nexus of mature technology and loss prevention an exciting time for the insurance industry. Wider use of the Internet of Things sensors is producing multiple benefits for insurers, including vast amounts of data on properties and a key marketing tool that carriers can use to attract and retain policyholders, he pointed out.

Besides preventing damage, the greatest attraction for property owners may be premium discounts. Chubb is still compiling data and has not yet said what the average credit is for commercial policyholders. But Sarma said that homeowners who install devices can see credits of 3% for sensors and as much as 8% for water-line shutoff devices.

Chubb, which Sarma said is the largest writer of high-end residential properties in the U.S., provides shutoff valves that will close the main supply line to the house as soon as a leak is detected anywhere in the home. A sensor sends a notice to the owner’s cellphone.

It’s perfect for those times when families go on vacation and can’t be there to notice a growing puddle on the floor, he noted.

Temperature alerters also have proven to be especially valuable for policyholders who have expensive wine collections. Freezing or high temperatures can ruin a pricey, 100-year-old bottle of vino.

The sensor devices have become such a part of Chubb’s long-term business strategy that it acquired StreamLabs last summer. The Australia-based company is considered one of the leading manufacturers of leak-detection and shutoff devices. quote out

Other insurers are buying into the trend. The president of Vyrd Insurance, a startup property insurer in Florida, has said the company’s business model calls for widespread use of water sensors that can help detect leaks and alert rapid-repair teams. The Hartford, Peninsula Insurance Services and other insurers also have begun deploying the systems.

And while news outlets have reported stories of IoT devices being hacked into, Chubb and its supplier have said its sensors are quite secure. For one thing, the sensors placed in commercial buildings are not wi-fi enabled, but operate through a standalone cellular system that incorporates LoRaWAN, a type of wide-area private wireless network, explained Gordon Hui, vice president of IoT product management for Hartford Steam Boiler.

“We’re not a startup. We’re not cutting corners. We take the longevity and security of this solution very seriously,” Hui said.

Hartford Steam Boiler, part of Munich Re, may be best known as a 150-year-old boiler company-turned-speciality insurer. But it also has manufactured IoT devices for loss prevention since 2014. The company realized that non-weather water damage is huge for insurers – as much as $16 billion a year, according to CoreLogic reports – and it’s better to predict and prevent than to clean up the mess.

“When we designed this solution, we talked to customers, and time and again, non-weather water continues to be the most frequent cause of loss for a lot of P/C carriers. And the numbers are truly astounding,” Hui said.

He said the company has not yet seen its devices used in claims litigation. But it’s possible, particularly in a state like Florida, where insurers have said that claims dispute litigation and inflated damage estimates by public adjusters have skyrocketed in recent years. Instead of dueling experts testifying about the apparent age of water or mold damage, the insurer could potentially refute claims by offering data from the water sensor – showing that no leak had been detected.

The next evolution, Chubb’s Sarma said, is leak detectors for roofs. Chubb has started installing sensors below the roof decking in some commercial buildings, recognizing that water infiltration from damaged roofs is one of also the largest loss drivers for insurers.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case  LA County Told to Pause $4B in Abuse Payouts as DA Probes Fraud Claims

LA County Told to Pause $4B in Abuse Payouts as DA Probes Fraud Claims  Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake

Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake  These Five Technologies Increase The Risk of Cyber Claims

These Five Technologies Increase The Risk of Cyber Claims