A tragic accident at a Massachusetts auto auction company is not covered by the insurance of the auto dealer that hired the auction company to sell the vehicle involved in the accident.

A federal appeals court has declined to perform “amazing feats of linguistic gymnastics” to create coverage where none was intended

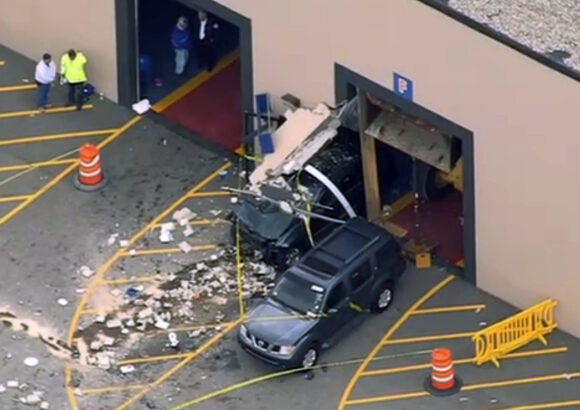

In April 2017, Nashua Automotive, a New Hampshire auto dealer, received a 2006 Jeep Grand Cherokee as a trade-in for a new vehicle it sold. Nashua arranged for a separate company in Massachusetts, Lynnway Auto Auction, to auction the Jeep. On May 3, 2017, while that Jeep was being put up for auction inside Lynnway’s facility, it accelerated into a crowd, killing five people and seriously injuring others.

Lynnway employee Roger Hartwell, who was seated in the driver’s seat of the Jeep, claimed that the vehicle accelerated uncontrollably despite his efforts to stop it. Hartwell was subject to a long series of suspensions of his driver’s license, although the parties dispute whether Hartwell’s license was suspended at the time of the accident.

Motorists Commercial Mutual Insurance Co. insured the Nashua dealership that owned the Jeep. The accident victims and their estates filed a series of lawsuits in Massachusetts state court, alleging several theories of liability against Lynnway, Hartwell, Nashua, and Nashua’s owner AutoFair, as well as others.

Motorists sought a declaration that its policies did not cover the auctioneer Lynnway or its employee Hartwell who was behind the wheel of the vehicle when it struck the victims. Defendants in this action included those who claim an interest in Motorists’ coverage: the victims, the auctioneer, and its employee.

Both sides moved for summary judgment, which the district court granted in favor of Motorists in 2021.

After a review of the defendants’ arguments spanning several policies and exclusions, the First Circuit Court of Appeals has now agreed with the district court that Motorists’ policies do not cover this accident.

Motorists provided a primary liability policy that covered AutoFair along with its affiliate Nashua Automotive and other AutoFair-affiliated dealerships as named insureds. The policy did not name Lynnway or Hartwell among the insureds. Motorists also provided a commercial umbrella policy that provided supplemental insurance above the primary policy’s limits to many of the same named insureds, including Nashua and AutoFair.

The primary policy included a garage coverage form that says Motorists will pay for bodily injury or property damage caused by an accident and resulting from garage operations involving the ownership, maintenance or use of covered autos. A New Hampshire auto business endorsement to this form changed the definition of an insured such that it included “anyone else while using with your permission a covered auto you own . . . except . . . someone using a covered auto while he or she is working in a business of selling, servicing or repairing autos unless that business is yours.”

The New Hampshire endorsement also added a suspended license exclusion that provides that the insurance does not apply where an insured is operating the vehicle while his or her driver’s license is under suspension or revocation.

The umbrella policy’s definition of “who is an insured” specifically excludes “any person employed by or engaged in the duties of an auto sales agency . . . that you do not operate.”

Motorists pointed to both the auto business exclusion and the suspended license exclusion as foreclosing coverage under the primary policy. It also argued that its umbrella policy’s “following form” endorsement provided auto coverage that is no broader than that provided for in the primary policy.

The district court agreed with Motorists on all three scores, granting summary judgment in its favor. The defendants appealed.

On appeal, both the Lynnway defendants and the victim defendants contended that the coverage provided by the broad insuring clause of the primary policy survived that policy’s auto business exclusion as well as its suspended license exclusion. They also insisted that the umbrella policy separately provided coverage.

As modified by the New Hampshire endorsement, the exclusion excepts from the definition of insureds “someone using a covered auto while he or she is working in a business of selling, servicing or repairing autos unless that business is yours [Nashua’s].” Defendants argued, first, that Lynnway was not “in a business of selling, servicing, or repairing autos.” Second, they argued that even if Lynnway were in such a business, that business was Nashua’s.

The appeals court completely dismissed the argument that Lynnway and its employee were not in the business of selling autos, finding that they were plainly engaged in that business as evidenced in part by Lynnway’s own articles of incorporation that state its purpose is “to auction, sell and distribute automobiles” and “to engage in the business of purchasing, . . . [and] selling . . . all types of new and used automobiles.”

The Lynnway defendants principally argued that an auctioneer who never takes title to the goods sold acts merely as a broker, rather than the seller of the goods. But the court dismissed this distinction, finding no legal support for the contention that the “business of selling autos” under New Hampshire law must be construed to encompass only the title-holding seller and to exclude auctioneers.

The court noted that under the “plain language of the policy,” the focus is not on whether Lynnway took title to the auto but instead on whether Hartwell and Lynnway were working in a business of selling autos. “A reasonable person understands that an auction is a sale, and thus that someone engaged in an auction business is engaged in a selling business,” the opinion states.

Quoting from a previous case, the court said it will “not perform amazing feats of linguistic gymnastics to find a purported ambiguity simply to construe the policy against the insurer and create coverage where it is clear that none was intended.”

As an alternative, defendants contended that any selling business in which Lynnway and Hartwell were engaged at the time of the accident was Nashua Automotive’s business. They argued that Nashua had an extensive business relationship with Lynnway and exerted some de facto control over the Jeep while it was being auctioned. They claimed that AutoFair had use of an office at Lynnway’s premises and could make certain decisions about how its cars were sold.

This contention fared no better than the first. The court found nothing in the policy suggesting that this type of control is equivalent to making the auction business Nashua’s business:

“They [Lynnway and its employees] were auctioning the Jeep. And it is undisputed that Nashua was not itself an auction house — it engaged with other entities, like Lynnway, for this purpose. So while Nashua can fairly be said to have retained Lynnway to sell its vehicle, we see nothing in that relationship to suggest that Lynnway’s independent auction business had been converted into an arm of Nashua’s business.”

Finally, the appeals court said the district court was correct that the umbrella policy applies only to the extent auto coverage is provided in the primary policy.

Top photo: This May 3, 2017 file still image taken from video provided by NBC Boston shows wreckage after a vehicle suddenly accelerated at the Lynnway Auto Auction and struck several people before it crashed through a wall of the building in Billerica, Mass. The business and company president James Lamb were each indicted Thursday, March 28, 2019, on five counts of manslaughter in connection with the fatal crash. (NBC Boston via AP, File)

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

One out of 10 Cars Sold in Europe Is Now Made by a Chinese Brand

One out of 10 Cars Sold in Europe Is Now Made by a Chinese Brand  Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud

Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud  Why 2026 Is The Tipping Point for The Evolving Role of AI in Law and Claims

Why 2026 Is The Tipping Point for The Evolving Role of AI in Law and Claims  US Will Test Infant Formula to See If Botulism Is Wider Risk

US Will Test Infant Formula to See If Botulism Is Wider Risk