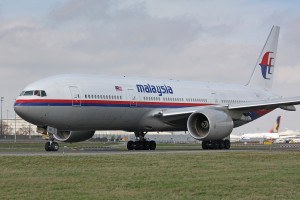

As the final hours of Malaysian Air Flight 370 remain wrapped in mystery, the question of who bears full liability for the jet’s disappearance is also unresolved.

This much is clear: Families of the 227 passengers aboard the flight that vanished on March 8 can recover some compensation from Malaysian Airline System Bhd even if the plane isn’t found. The airline is liable under international treaty for as much as $175,000 per passenger, and possibly more.

For survivors to capture significantly greater damages, wreckage would probably have to be located and a narrative of the plane’s demise assembled. Several scenarios have been offered for the flight’s disappearance, including hijacking, intentional downing or an on-board fire. Evidence of any of these could open avenues for family members to sue.

“The disappearance of Flight 370 remains a mystery. The legal claims against Malaysia Airlines — those are not a mystery,” said Robert Hedrick, a pilot and air-disaster lawyer in Seattle. “If the wreckage is located, the evidence may establish liability of other parties.”

“The disappearance of Flight 370 remains a mystery. The legal claims against Malaysia Airlines — those are not a mystery,” said Robert Hedrick, a pilot and air-disaster lawyer in Seattle. “If the wreckage is located, the evidence may establish liability of other parties.”

Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak narrowed speculation today, saying that based on satellite data, the plane ended up in the Indian Ocean west of Perth, Australia — ruling out theories that it took a detour over Asia.

“This is a remote location, far from any possible landing sites,” Najib said at a news conference in Kuala Lumpur. “It is therefore with deep sadness and regret that I must inform you that according to this new data, flight MH370 ended in the southern Indian Ocean.”

Search Plane

An Australian search plane has found two objects, one circular and one rectangular, in the southern Indian Ocean, Malaysian Acting Transport Minister Hishammuddin Hussein said today.

The Montreal Convention of 1999, an international treaty that covers air travel, requires carriers to pay damages for each passenger killed or injured in an accident, even if its cause is unknown. By those rules, the airline’s liability could stand at more than $40 million.

Damages Capped

Under the convention, claims against the airline will probably be litigated in China and Malaysia, the home countries of most of the passengers on the Kuala Lumpur-Beijing route, and both signatories to the pact. The treaty caps an airline’s damages at the equivalent of about $175,000 if the carrier can prove it wasn’t negligent or that a third party, such as terrorists or a manufacturer, was solely at fault. If it can’t mount such a defense, its liability could be much higher.

Survivors’ best chance for seeking more would be to find a way to sue in the U.S., where awards and settlements can be more generous than in the two Asian countries.

“The U.S. is always the best choice to file a lawsuit,” said Hao Junbo, a Beijing-based lawyer who specializes in aviation law. “The families may try and take a shot there. The problem is we haven’t seen any evidence to link it to the U.S. to file a claim there.”

One such scenario, lawyers said, would be for plaintiffs to allege that the missing 777’s manufacturer, Chicago-based Boeing Co., was at fault. John Dern, a Boeing spokesman, declined to comment on any possible liability issues connected to Flight 370.

Terrorism

Should terrorism emerge as a possible cause, survivors’ lawyers could seek to recover funds from terrorist groups and their sponsors.

Malaysian Air said that while its insurers are studying the issue of compensation based on the Montreal Convention, it is considering an advance payment to all the families “in the coming weeks.”

“Our top priority remains to provide any and all assistance to the families of the passengers and crew,” the airline said in an e-mailed statement.

The carrier said it has “adequate insurance coverage in place to meet all reasonable costs” of the disaster, including assisting families amid the search. It has already made financial-assistance offers to families of about $5,000 each.

Insurer’s Payments

Munich-based Allianz SE, Malaysian Air’s lead insurer on the lost aircraft, said it has made initial payments into a trust account, on the aircraft and on airline liability, which it said is routine.

Families have sometimes received compensation before a plane’s fate is learned, such as when Air France Flight 447 vanished between Rio De Janeiro and Paris in 2009. While wreckage was found floating in the sea days later, it took two years before the jet’s black-box recorders were discovered at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, from which investigators pieced together pilots’ struggles to recover from a stall.

In the case of Flight 370, the absence of evidence such as wreckage, complete flight data and cockpit recordings may make it difficult for Malaysian Air to exonerate itself and avoid additional damages, said Hedrick. An unsolved mystery would also make it harder for families to determine whether others beyond the airline may share responsibility for their loss.

In Malaysia, as in many U.S. states, a missing person can be declared dead after they’re absent, without evidence they’re alive, for seven years. The period in China is usually two years, said Hao, the Beijing lawyer.

Disasters

In disasters or other incidents in which someone would be presumed to have died, courts can declare missing persons dead within weeks or months. Some of the victims of Pan Am 103, which was destroyed by a bomb over Lockerbie, Scotland, and many of those killed in the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks were quickly declared dead although their bodies weren’t recovered.

There were 153 Chinese passengers aboard Flight 370, according to the airline. Chinese families are likely to choose to make their claims in their home country, Hao said.

“Chinese courts, Chinese judges will be more sympathetic to the Chinese victims,” said the lawyer, who represented families of a China Eastern Airline Corp. flight that crashed in 2004.

That case, in which Hao said he represented the families of 32 crash victims, was the first airline disaster lawsuit to be accepted by a Chinese court. Hao settled the suit, in which the settlement wasn’t disclosed.

The airline is likely to have an interest in settling with families rather than fighting in court, said Ravindra Kumar, a Kuala Lumpur-based lawyer at Raja, Darryl & Loh.

“I don’t think they want further publicity and would certainly try and resolve this amicably,” Kumar said.

(With assistance from Oliver Suess in Munich and Kevin Hamlin in Beijing.)

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

These Five Technologies Increase The Risk of Cyber Claims

These Five Technologies Increase The Risk of Cyber Claims  Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says

Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says  Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case  Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake

Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake