The alarms started sounding just seconds after Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 took off on March 10 from Addis Ababa with 157 people on board.

As speed and altitude readings started going haywire, a device known as a stick shaker activated on the left side of the cockpit, where the captain sits. The mechanism makes a loud noise and rattles a pilot’s control column to warn of an impending aerodynamic stall.

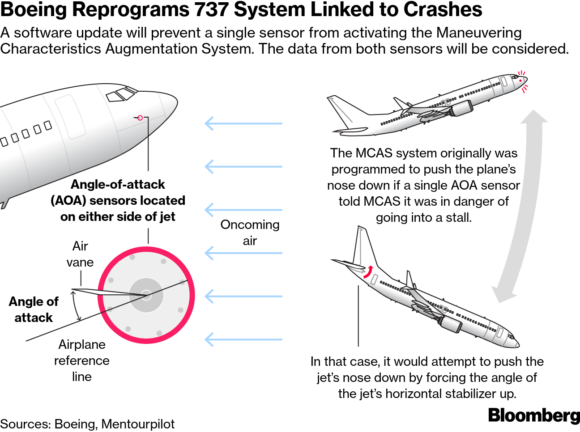

But the Boeing Co. 737 Max wasn’t about to stall. Instead, a computer was getting erroneous readings from a sensor mounted like a weather vane on the jet’s nose. The malfunction triggered an anti-stall feature that forced the plane into a dive — the same system that was implicated in a crash less than five months before in Indonesia that killed 189 people.

To counteract it, the Ethiopian Airlines pilots responded with at least some of the steps that Boeing and the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration recommended after the first accident. But amid a chorus of confusing alarms, they also made a critical oversight as they struggled for control, according to three pilots with experience in accident investigations: They left the engines set nearly to maximum.

“The thrust was full bore the whole way,” said Roger Cox, a former accident investigator at the National Transportation Safety Board, who flew earlier models of the 737 while working as an airline pilot. “That is extremely curious.”

Ethiopian Transport Minister Dagmawit Moges said in a press conference Thursday that the pilots followed proper procedures issued after the October crash of a Lion Air jet and recommended that Boeing review its flight-control system.

Ethiopian safety officials stopped short of saying the plane needs a redesign. Boeing was little changed Friday at $394.37 at 11:02 a.m. in New York trading. The shares have fallen 6.7 percent since the Ethiopian accident.

Ethiopian Airlines Group is reconsidering its order for 25 additional 737 Max jetliners from Boeing, in part because of the “stigma” surrounding crashes, Tewolde GebreMariam, the state-owned carrier’s chief executive, said in an interview Friday with Bloomberg News. It may be “a hard sell for us to convince our customers” to continue flying the plane, GebreMariam said.

The two disasters in five months have pushed Boeing into one of the biggest crises in its century-long history. The crash in Ethiopia resulted in the worldwide grounding of the 737 Max, the revamped version of a plane model that accounts for a third of Boeing’s operating profit. The accidents also prompted multiple investigations and reviews — including a criminal probe led by the U.S. Justice Department — of how U.S. regulators certified the flawed anti-stall system, known as MCAS.

The groundings are piling pressure on Boeing to come up with a fix that will keep pilots from having to make such complicated, split-second decisions to keep the 737 Max aloft. The company is redesigning its software and expects to complete the work within weeks. Among other changes, the update will keep the safety system from kicking in when only one of the sensors detects a stall.

“We at Boeing are sorry for the lives lost in the recent 737 Max accidents,” CEO Dennis Muilenburg said in a video. The Chicago-based planemaker blamed the accident on “a chain of events” and acknowledged the sensor malfunction.

Near-Maximum Thrust

At near-maximum thrust, the plane became more difficult to fly, multiplying the problems created by the flaw in the 737 Max’s software, according to pilots who reviewed a preliminary report issued Thursday by Ethiopia’s Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau. High speed also made it impossible to recover in the final seconds when the plane’s nose pointed downward into their final, high-speed dive.

“They exacerbated it,” said Jeffrey Guzzetti, the former director of the FAA’s Accident Investigation Division.

The Ethiopian report clearly showed that MCAS — the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, a safety measure added to the new plane to prevent it from dangerous stalls — had activated multiple times. That was similar to the Lion Air crash.

Sensors in the aircraft that report how high its nose is pointed relative to oncoming air varied by almost 60 degrees. One of the “angle-of-attack” gauges read 15.3 degrees, likely an accurate reading for a plane taking off. The other erroneously read 74.5 degrees — which would suggest a plane pointing almost straight skyward.

Lost Control

Even though pilots took at least some of the steps recommended by Boeing and the FAA to counteract MCAS, they were confused and ultimately lost control, according to the report.

“As pilots have told us, erroneous activation of the MCAS function can add to what is already a high workload environment,” Muilenburg said in his statement. “It’s our responsibility to eliminate this risk. We own it and we know how to do it.”

Every plane crash typically involves multiple contributors, and the detailed Ethiopian report chronicles many factors that occurred over a matter of minutes leading to the accident.

“Everyone can talk about it from a desk, but when you see it happening it’s another thing,” said Dennis Tajer, a spokesman for the Allied Pilots Association at American Airlines. “What steps were taken, what steps were missed? Those are all things we’re going to be looking at for several weeks.”

Excess Speed

Pilots interviewed by Bloomberg didn’t agree completely about the factors.

Some took issue with Ethiopia’s transport minister, saying the Ethiopian Airlines pilots had actually failed to properly follow the procedures. Other pilots said the flight crew’s actions were understandable given the chaotic situation.

But they all agreed that the speed was critical.

The plane took off at 94 percent of full power, according to the report. That is normal for liftoff, but pilots then typically pull back the power soon afterward. Even though the captain called for setting the speed at 238 knots, or 274 miles per hour, about a minute after takeoff, the engine thrust remained at the same level for the entire short flight, according to the report.

Before it picked up speed in its final dive, the plane was flying as fast as 365 knots, or 420 miles an hour — almost twice the usual top speed at that low altitude. In addition to the multiple warnings prompted by the MCAS failure, the pilots were also getting audible alerts indicating they had exceeded the safe flying speed, according to the report.

The Ethiopian crew followed one important step required to deal with an MCAS failure when they shut off power to the motor the system uses to automatically drive down the nose, according to the report.

However, at the high speed at which they were flying, it became much harder to adjust the plane’s pitch manually, said John Cox, president of Safety Operating Systems and a former airline pilot.

Control Column

For more than two minutes during the flight with the trim system powered off, the crew had to apply strong pressure to their control column to continue flying, according to the report. Normally, pilots would adjust the wing at the tail of the plane to make the nose point upwards and reduce that pressure.

During that time, the captain asked the copilot to try making adjustments — known as trimming — manually. “The first officer replied that it is not working,” according to the report. The two wheels that pilots turn by hand to trim would have been “very hard to move or impossible” at that speed, John Cox said.

While it’s not clear from the report exactly what steps the pilots took, their struggles to keep the plane climbing apparently led them to switch power back on to the trim system. About 30 seconds before they crashed, it was activated by the pilots to slightly raise the nose.

Five seconds later, MCAS engaged again, once more pushing down the nose. At that speed, they couldn’t overcome the dive using their control column alone, according to John Cox and Guzzetti. For reasons that haven’t been explained, they didn’t try to also trim the plane using switches on their control yokes.

The plane eventually pointed down by 40 degrees and the plane reached speeds of 575 miles per hour.

“You can’t read the transcript and not put yourself in the cockpit,” Tajer, of the Allied Pilots Association, said. “Every honest pilot says, I could see me right there, doing that, even if it was not a good thing, or saying, yeah that makes sense.”

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case  Elon Musk Alone Can’t Explain Tesla’s Owner Exodus

Elon Musk Alone Can’t Explain Tesla’s Owner Exodus  Cape Cod Faces Highest Snow Risk as New Coastal Storm Forms

Cape Cod Faces Highest Snow Risk as New Coastal Storm Forms  China Bans Hidden Car Door Handles in World-First Safety Policy

China Bans Hidden Car Door Handles in World-First Safety Policy