The grounding of a luxury cruise ship off the coast of Greenland on Monday highlighted the irony of touring the fast-warming Arctic on vessels powered by fossil fuels, the main culprit in climate change. But the incident also underscores the recent growth of marine traffic in the region, a trend that raises the risk of accidents and pollution in hard-to-reach places.

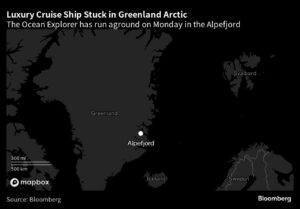

Global warming is destroying vast tracts of polar ice, opening previously frozen sea routes through the Arctic for longer periods. In the case of Greenland — where the Ocean Explorer was mired in glacial silt in a remote fjord before finally being freed Thursday — cruise ship traffic has risen 50% in the last year, to about 600 ships, according to Brian Jensen of the Danish military’s Joint Arctic Command.

That trend is seen across the Arctic. “From the period of 2009 to 2018, ship traffic on a pan-Arctic scale doubled,” said Paul Berkman, lead author of a 2022 report on the subject published by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “Ship traffic is increasing as sea ice is decreasing.”

The impact is being felt on remote ecosystems and communities as ships burning marine diesel, or methane-emitting liquefied natural gas, increasingly criss-cross the top of the globe. Some studies show the carbon footprint of cruise ships, per passenger, is bigger than that of passenger jets. Globally, maritime transport emits more CO2 than Germany.

The impact is being felt on remote ecosystems and communities as ships burning marine diesel, or methane-emitting liquefied natural gas, increasingly criss-cross the top of the globe. Some studies show the carbon footprint of cruise ships, per passenger, is bigger than that of passenger jets. Globally, maritime transport emits more CO2 than Germany.

More ship traffic also means a higher risk of accidents in remote, poorly mapped areas known for harsh and unpredictable weather conditions.

A 2021 report on Arctic marine disasters showed a 42% increase in accidents between 2005 and 2017 north of 58 degrees latitude, which encompasses the Arctic as well as some sub-arctic territory. The report acknowledged gaps in the data, noting that not all Arctic states provided information.

More than 40 expedition vessels — smaller ships capable of traversing narrow channels and shallow waters — were exploring the Arctic this summer, led by 20 different operators, according to Cruise Industry News. Popular routes included those across Canada’s Northwest Passage and along the coasts of Greenland, Norway and the Svalbard Archipelago. Of even greater concern, though, are much larger conventional cruise ships capable of carrying thousands of passengers.

The Icelandic Coast Guard is “very worried” about the rising number of such vessels around Iceland and the Arctic, spokesperson Asgeir Erlendsson said. “If any of those big ships run into trouble, there are many people on board and a rescue mission can take a long time and needs to involve a lot of people,” he said. “This requires international cooperation and using resources like the fishing fleet if needed. Rescuing with a helicopter for instance will be very time consuming under such circumstances.”

Greenland’s parliament will probably start talks about extending protection of land areas to also include waters, Vivian Motzfeldt, the country’s minister for business, trade and foreign affairs, told the country’s main newspaper, Sermitsiaq.

“The current situation clearly shows that we must and need to work to ensure there are strict, clear and unambiguous legal requirements” starting from the next cruise season, she told the media.

The Ocean Explorer was pulled free by a fishing expedition vessel before a Danish ship sent to rescue people on board was able to reach the ship. Other countries’ Arctic territories are even larger and more difficult to access. The Canadian Coast Guard has seven or eight icebreakers available each year to serve 162,000 kilometers (101,000 miles) of northern coastline, delivering supplies and providing search-and-rescue support.

Fewer than half of Canada’s primary Arctic shipping corridors have been surveyed to modern standards, said Rashaad Bhamjee, superintendent of navigational programs for the Canadian Coast Guard. Less than 16% of its Arctic waters have been properly mapped. “The worst case scenario, for us, would be having a large cruise ship, or a tanker, run aground or breach its hull.”

The need to protect the region from environmental disasters has led some Arctic governments, including Canada, the US and Greenland, to impose bans on oil and gas exploration.

“We simply don’t have the technology or the capacity to respond to any sort of emergency or accident,” Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told Bloomberg Green in an August 25 interview about the Arctic. “You think of Deep Water Horizon, or things that happen in the Gulf of Mexico that at least aren’t hindered by sea ice and incredible remoteness — you couldn’t do it.”

Cargo shipping is also increasing, as melting ice opens routes that can shave days or even weeks off southerly routes. Russia has made transport through its Northern Sea Route a key pillar of future economic development. China’s Arctic policy includes a Polar Silk Road to facilitate travel through the region. Military interest in the region is on the rise since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. All of it spells increased future risks.

Other potential consequences include ships colliding with marine mammals, light and noise pollution, and the spread of diseases to remote Indigenous communities.

In the case of the Ocean Explorer, no oil appears to have leaked and the ship was freed with no apparent damage to the hull, and no injuries. Still, it’s a cautionary tale about the potential for disaster in what is still one of the most remote places on Earth.

“Our worst-case scenario is a large cruise vessel with 8,000 to 9,000 people on board having an emergency in an isolated area,” said Tore Wangsfjord, chief of operations at the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre North-Norway, which handles search-and-rescue operations over an area extending to the North Pole.

Of the Ocean Explorer, he added, “Multiply the number of people on board by 25, and you can imagine the situation.”

–With assistance from Brendan Murray and Christian Wienberg.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings

FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings  Tesla Sued Over Crash That Trapped, Killed Massachusetts Driver

Tesla Sued Over Crash That Trapped, Killed Massachusetts Driver  US Will Test Infant Formula to See If Botulism Is Wider Risk

US Will Test Infant Formula to See If Botulism Is Wider Risk  Portugal Rolls Out $2.9 Billion Aid as Deadly Flooding Spreads

Portugal Rolls Out $2.9 Billion Aid as Deadly Flooding Spreads