The Nebraska Supreme Court in Barnes v. American Standard Insurance Company of Wisconsin, 297 Neb. 331, 900 N.W.2d 22 (2017) recently considered whether an insurance company’s cancellation of an auto policy by certified mail permitted the granting of summary judgment on the cancellation issue.

In this case, Jimmy Barnes was involved in a motorcycle-motor vehicle accident. Prior to the accident, Barnes had three motor vehicle insurance policies issued by American Standard, including the motor vehicle policy in question. The insurer, American Standard, issued three cancellation notices for the three policies on September 18, 2013. The cancellations occurred because the bank account from which American Standard electronically withdrew the monthly premium payments had insufficient funds. Alternatively, the bank may have otherwise rejected the transaction at the time that the premiums were due. Because of this, notices were sent to Barnes at his mailing address, advising that the three policies would be cancelled effective October 1, 2013 unless the premium payments were received. American Standard mailed the cancellation notices to Barnes by certified mail. However, Barnes alleged that he did not receive the cancellation notices. Mr. Barnes was involved in a motor vehicle accident on October 10 where he was struck by an underinsured motorist while riding his motorcycle. The accident occurred after the October 1 cancellation date.

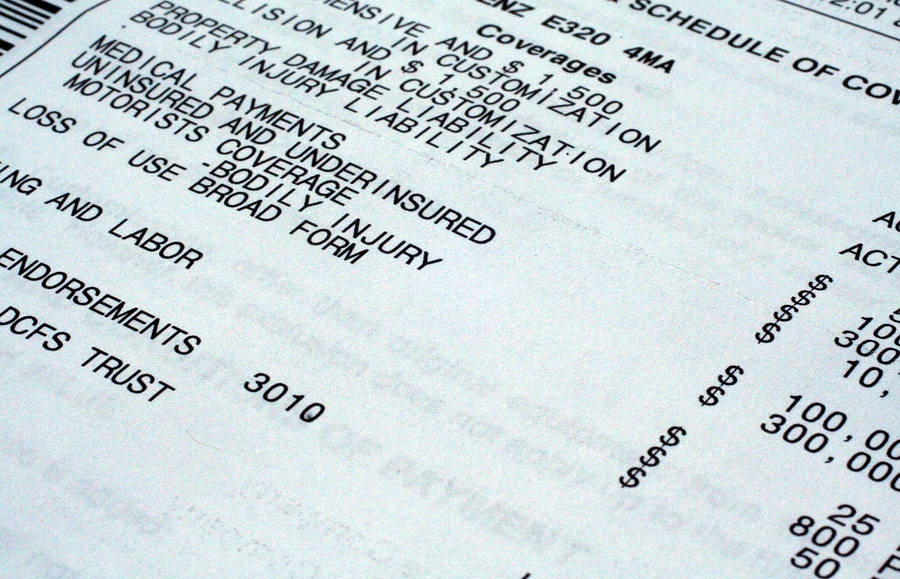

Barnes received serious injuries as a result of the accident. The tortfeasor’s insurer paid its policy limits of $100,000 because of the injuries and Barnes presented a UIM claim to American Standard. American Standard rejected the UIM claim because of the prior cancellation. Thereafter, Barnes sued American Standard, alleging the policy was not cancelled.

American Standard filed a motion for partial summary judgment on the issue of whether American Standard’s notice of cancellation was sent by certified mail. The court convened a hearing on the motion for partial summary judgment, at which time Barnes introduced into evidence his affidavit, blank U.S. Postal Service forms 38-11 and 3800, a copy of American Standard’s mailing log on postal form 3877, American Standard’s responses to Barnes’ request for production of documents and the cancellation notices dated September 18, 2013. American Standard offered as exhibits the cancellation notices, two affidavits from American Standard employees regarding American Standard’s mailing procedures, various documents regarding American Standard’s policy cancellation procedure, a demonstrative exhibit used to illustrate certified mail, a copy of American Standard’s mailing log form 3877 dated September 18, 2013, and a U.S. Postal Service Certificate of Mailing for a piece of first class mail relating to Barnes’ homeowners’ policy.

U.S. Postal Service form 3877, relied on by both Barnes and American Standard, indicated that there were three pieces of mail sent to Barnes. Form 3877 had a space on the form to indicate what type of service was applied to the mail but the box for “certified” was not checked. Form 3877 also had a space where the sender was to include the addressee’s information and stated “addressee” (name, street, city, state, and zip code). Although American Standard had supplied on the form Barnes’ name, city, state, and zip code, it did not include his street or house number. Form 3877 contained the Postmaster’s stamp, date, tracking numbers, fees and postal worker signatures.

Nebraska statute required the cancellation notice to be sent by registered or certified mail to the named insured. See Nebraska Revised Statute §44-516(1) (reissue 2010). Under the statute, insurance companies were not required to establish that the named insured received the cancellation notice. During the hearing the court noted that in the context of federal tax cases, other courts had determined that form 3877 was an acceptable method to prove that an item was sent by certified mail. Although the court noted the defects in the submitted form 3877, the court nevertheless determined that the “majority of the evidence in this case established [American Standard] complied with Nebraska Revised Statute §44-516 by sending the cancellation notice to [Barnes] via certified mail on September 18, 2013.” Therefore, American Standard’s motion for partial summary judgment was granted. The Nebraska Supreme Court rejected the grant of summary judgment and remanded.

The parties focused on the defects in form 3877. The District Court had acknowledged that American Standard failed to check the certified box and neglected to include Barnes’ street address on the form. Nevertheless, the District Court found that the defects were overcome by American Standard’s presentation of other evidence in the form of employee affidavits indicating mailing procedures and that American Standard’s cancelled procedures were followed. The street address on the cancellation notices on policies not at issue in the case created a strong inference that the cancellation notices were all sent to the same address, even though the notice in question did not have the address on it. Form 3877 did show that three pieces of mail (presumably the cancellation) were sent to Barnes.

The Nebraska Supreme Court began its analysis by noting that the burden of establishing an effective cancellation before a loss was on the insurance company. Therefore, it was American Standard’s burden to demonstrate compliance with the statute. Reviewing the trial court record, the Supreme Court found there was no actual direct evidence that the notice of cancellation was mailed certified to Barnes within the context of a motion for summary judgment. The court held that the weight to be accorded American Standard’s other evidence had to await resolution at trial. Had American Standard checked the certified mailing box, the proof of a certified mailing would have been greatly enhanced.

The Nebraska Supreme Court found that the Nebraska legislature had specifically selected that the notice of cancellation be mailed by “registered or certified mail.” The court found informative the reasoning of the Illinois Supreme Court as discussed in the Illinois Court of Appeals case of Hunt v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 213 Ill. App. (1st) 120, 561 ¶36, 994 N.E.2d 561, 570-71, 373 Ill. Dec. 792, 801-02 (2013):

[T]he Supreme Court stated “[i]t is apparent from the wording of the provision in the context of the insurance co. that the purpose of the statute is to protect the insured from cancellation of his insurance without his knowledge. To accomplish this purpose the legislature could have required insurance companies to prove receipt by the insured. But, by enacting this section, the legislature clearly sought to strike a balance between the interest of the insured in being informed of a cancellation of his insurance policy and the burden that would be put on an insurance company to prove receipt by the insured. [Citation omitted]. In striking a balance between insured persons and insurers, the legislature gave insurance companies a “very low threshold of proof” relating to the mailing of cancellation notices, requiring only that the insurer show proof of mailing on a recognized United States Post Office form or form acceptable to the United States Post Office or other commercial mail delivery service [citation omitted]. The court then held that a finding that “the statute implicitly allows an insurance company to use other evidence to show it maintained the proof of mailing when the statute explicitly requires it to maintain such a form would disturb the balance that the legislature sought to achieve in enacting [the statute].

The Nebraska Supreme Court found the quoted language above to be relevant in its case disposition.

By adding those terms of art, the Nebraska legislature deliberately chose those services. Taking the inferences in favor of Barnes as the non-moving party, the court found that the evidence submitted by American Standard did not establish directly that it mailed the notice of cancellation by certified mail and it was not entitled to judgment as a matter of law.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Founder of Auto Parts Maker Charged With Fraud That Wiped Out Billions

Founder of Auto Parts Maker Charged With Fraud That Wiped Out Billions  One out of 10 Cars Sold in Europe Is Now Made by a Chinese Brand

One out of 10 Cars Sold in Europe Is Now Made by a Chinese Brand  FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings

FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings  Uber Jury Awards $8.5 Million Damages in Sexual Assault Case

Uber Jury Awards $8.5 Million Damages in Sexual Assault Case