Cyberattacks in Ohio have disrupted airport flight displays, led to the shutdown of a help line during a winter storm and cut off access to police investigation reports temporarily.

The Buckeye State is fighting back.

Its first volunteer cyber reservists will be assembled in January, ready to parachute in to get local governments back up and running after computer systems are hacked. The move is among the latest defense plans of local governments across the U.S. as dozens of states and municipalities face cyberattacks this year.

“What we’re seeing is issuers are really increasing cyber defense investing,” said Orlie Prince, a vice president and senior credit officer at Moody’s Investors Service. “Governments are testing their systems and making sure that they can operate in the event of their attacks. Hacking attempts are constant.”

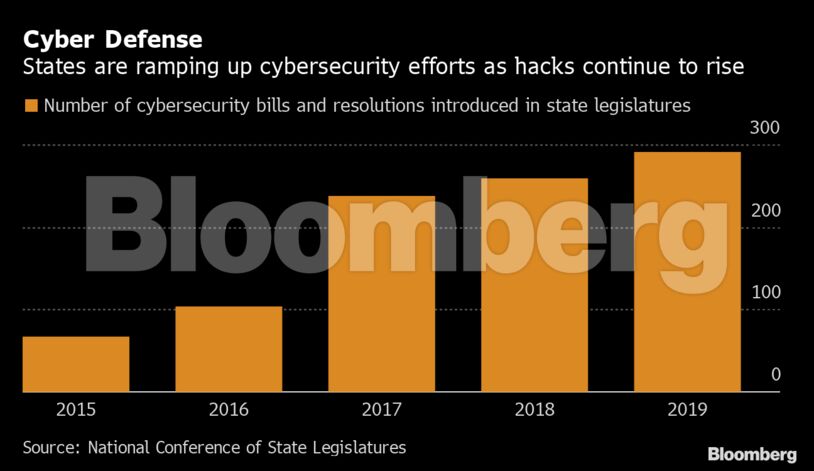

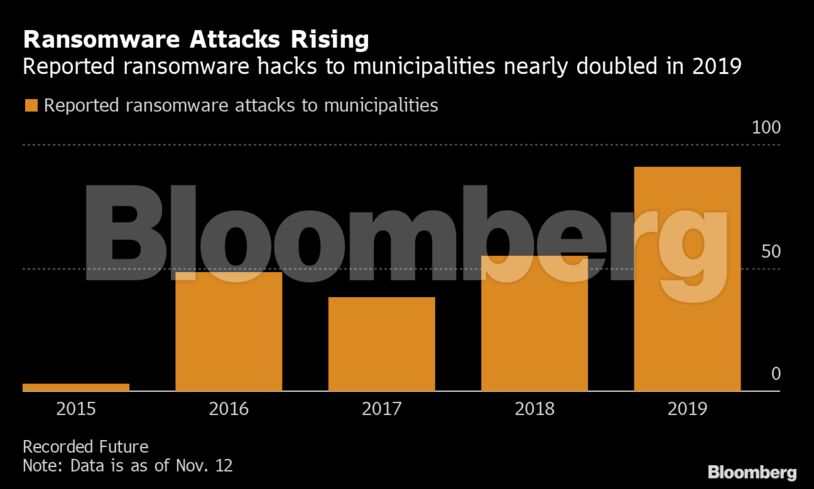

Louisiana is still recovering from a ransomware attack last week, its most significant cyber-event ever. It’s not alone: At least 91 cyber attacks have targeted municipalities this year, nearly double the amount in all of 2018, according to data collected by cybersecurity researcher Recorded Future. State lawmakers nationally have introduced or considered almost 300 bills or resolutions related to cybersecurity in 2019, up from about 65 in 2015, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Not only will Ohio’s cyber reservists help restore operations and services, but these information technology specialists may help the finances of towns, schools and airports. Establishing a cyber defense group is seen as a credit positive for local governments, according to Moody’s. The state support may prove beneficial for communities that lack resources or technical expertise to combat this growing threat, according to the ratings firm.

Even as governments globally are “vulnerable” to cyberattacks, the risk to credit ratings is “limited,” Moody’s said in a report on Monday. The New York-based rater assesses cyber risk for governments by looking at vulnerability to an attack as well as the kind of fiscal and reputational impact of such an event. Moody’s rates $3 trillion of state and local government debt subject to cyber risk, according to the report.

Still, Moody’s is factoring in cybersecurity measures as part of its governance assessment, citing the “precipitous rise” in such incidents over the last couple of years. Attacks cost Atlanta millions of dollars, temporarily prevented Baltimore from collecting water bills and property taxes, and one led to money stolen from an Oklahoma retirement fund.

Last week, Louisiana took down state servers as officials responded to an attack that affected 500 of the state’s 5,000 servers and more than 1,500 of its 30,000 computers, according to its deputy chief information officer. Several state agency services haven’t operated for a week, and some motor vehicle offices opened on Monday for the first time since the hack.

Louisiana’s attack came as state officials were certifying a tight gubernatorial election. While the vote tally isn’t expected to be affected, the incident highlights the importance of municipal cybersecurity efforts as the U.S. heads into a presidential election year.

State governments are responding in various ways. Washington state leads cybersecurity audits to help local governments catch weaknesses. Nevada and Montana have set up rules on access to student data.

Ohio’s plan follows the creation of similar cyber defense groups in states including Michigan. Ohio Governor Mike DeWine signed a bill to create the cyber reserves in October after several cybercrime incidents in the state.

In 2018, hackers hit police servers in Riverside, a town just a few miles outside Dayton. This year, a 311 help line in Akron was shut down amid a January snowstorm, and flight and baggage display systems were temporarily down in April at Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, according to local news outlets.

“If it was a physical world event, we’d fight it with every resource we have, and we should treat a cyber-based attack with the same seriousness,” said Frank LaRose, Ohio’s secretary of state, who proposed the idea as a state legislator last year. He likens the cyber reservists to local volunteer fire departments. More than 60 volunteers have registered, and more have expressed interest, according to Ohio’s Adjutant General’s Department.

“There’s no need for a response force to be on full-time duty but when there’s a strike, have them available,” LaRose said. “Anything that makes our municipal governments more resilient would be considered advantageous.”

Ohio will earmark $100,000 in fiscal 2020 and $550,000 in fiscal 2021 to operate reserve groups, which “represents strong management and governance,” according to a November report by Moody’s, which rates Ohio Aa1 rating with a stable outlook.

While Moody’s hasn’t downgraded municipal-bond issuers based solely on cybersecurity concerns, S&P Global Ratings lowered its outlook in April to negative for the Princeton Community Hospital in West Virginia after the impact of a fiscal 2017 cyberattack was reflected in its unrestricted reserves. S&P has a BBB+ long-term rating on Princeton.

Ohio’s steps to centralize cybersecurity efforts is conducive to entities reporting and sharing experiences in the future for coordinated responses, said Frank Shafroth, director of the center for state and local government leadership at George Mason University.

“It won’t deter hackers, but they’re likely to get a much more sophisticated challenge coming from the state,” Shafroth said.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Why 2026 Is The Tipping Point for The Evolving Role of AI in Law and Claims

Why 2026 Is The Tipping Point for The Evolving Role of AI in Law and Claims  These Five Technologies Increase The Risk of Cyber Claims

These Five Technologies Increase The Risk of Cyber Claims  One out of 10 Cars Sold in Europe Is Now Made by a Chinese Brand

One out of 10 Cars Sold in Europe Is Now Made by a Chinese Brand  Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo

Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo