Hurricane Andrew hit South Florida with winds topping 160 mph on August 24, 1992, devastating several communities before striking the Louisiana coastline.

According to the Insurance Information Institute (III), prior to Hurricane Katrina, Andrew caused the largest insured losses in U.S. history—$15.5 billion ($22.9 billion in 2011 dollars by III’s estimate). The hurricane resulted in 700,000 claims and destroyed or damaged 125,000 homes and 82,000 businesses, according to catastrophe modeling firm AIR Worldwide.

Gary Kerney, assistant vice president of Verisk’s Property Claims Services, says the catastrophic damage the storm inflicted on Florida and the Gulf Coast was unlike anything insurers had ever seen.

“Back in 1992, when Hurricane Andrew made landfall, it became the costliest catastrophe that the insurance industry had ever faced,” said Kerney. “It far exceeded the losses caused by Hurricane Hugo, which had made landfall in South Carolina four years earlier, and there were no other ‑‑ that I can recall, at least ‑‑ billion‑dollar catastrophes at that time. So Andrew, in and of itself, was quite an event for the insurance industry.”

According to the III, several changes within the insurance industry in the last two decades can be directly attributable to the 1992 hurricane. These include:

- Coastal exposure underwriting scrutiny

- Larger role of government in insuring coastal risks

- Introduction of hurricane and percentage deductibles

- Strengthened building codes

- More reliance and trust in catastrophe modeling

In 1992, the P/C market was comprised of 6 percent domestic carriers and 94 percent foreign or national insurance companies domiciled out of state, according to III statistics.

After Andrew, the out-of-state insurers learned they had underestimated their exposure. Some insurers became insolvent and others cancelled or non-renewed policies, or requested large rate increases in order to address the severity of the losses, III reports.

Legislators worked quickly to make sure moratoriums were placed on these types of actions, resulting in insurers adopting stricter underwriting standards. According to the III, by 2011 national writers comprised just 18 percent of the market and the then insurer of last resort, Citizens Property Insurance, had become the largest property insurer in the state of Florida.

The origination of percentage and hurricane deductibles can be traced back to Hurricane Andrew as well.

Percentage deductibles are self-adjusting because they reflect the insured’s home value, based on changing construction costs of rebuilding a damaged property.

According to III, 18 states currently have hurricane deductibles: Alabama, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia and Washington D.C.

Florida currently ranks high in the adoption of strict building codes and their regulation according to the Institute of Business and Housing Safety, but that wasn’t the case in 1992, Kerney said.

“Back in 1992, there wasn’t so much … with respect to the kind of protection that building codes are looking to provide today. And my recollection …, especially in the Miami‑Dade County, or back then it was known as Dade County, was that the building departments were a little overwhelmed with the number of folks that were looking for permits to begin construction,” Kerney said.

The subsequent permit delays frustrated some home and building owners.

“One of the things, I think, that concerned me and concerns others that can recall that far back, 20 years ago, is that a lot of folks got frustrated and went ahead and made repairs on their own. We don’t know how those self‑repaired buildings will fare in the event of another hurricane of the magnitude of Hurricane Andrew in the same sections of Florida,” said Kerney.

Russel Lageza, a South Florida attorney who worked at the Florida Department of Insurance in the past, said that Hurricane Andrew and other hurricanes that followed proved that big hurricanes can happen.

While he agrees that building codes have improved, it may not matter if homeowners can’t afford to upgrade their homes; citing dwindling wind mitigation credits that used to be available.

“Yes, we’re definitely more hurricane-ready in our building codes here in Florida but none of that will matter much if consumers don’t have the discounts and incentives to upgrade their homes to code. Those seem to be disappearing very, very quickly,” Lageza said.

The plaintiff attorney also noted narrowing coverage and more aggressive insurer stances on disclaiming coverage.

“…The result for the consumer in Florida has been a whole lot less coverage over the years for a whole lot more money,” Lageza said.

A focus on catastrophe modeling was another result of the 1992 hurricane.

Prior to Hurricane Andrew, insurers estimated the size of future losses using “experience” data based only on what happened in the past, the III reported. Actuaries adjusted recent history to reflect current trends. “Hurricane Andrew proved that past data is a poor gauge for future catastrophe exposure”, the III stated in a recent report on the subject. That’s because past data failed to account for population density and increasing construction and property values along coastlines, the insurance organization opined.

“Hurricane Andrew was really the first time, I think, that the modelers were out there trying to show their wares, and in the beginning, there wasn’t a lot of faith put in the kinds of numbers that the modelers were coming up with,” Kerney said.

“In the ensuing 20 years, the modelers have made great strides, and I think they provide a really valuable service today to the insurers, the reinsurers and the policyholders, because now everybody understands the risk and the exposure,” Kerney said.

Kerney recalls other issues related to hurricane, including officials’ perceived delays in response.

“I remember Kate Hale didn’t ask where FEMA was, Kate Hale asked where the cavalry is. And, you know, the insurance industry was there way before FEMA was. Again, it is no knock against FEMA; it was the largest disaster they had ever faced in any of their lifetimes in terms of being FEMA employees and trying to bring disaster assistance, and they were thinking on their feet and trying to figure out the best way to surround this thing and get the aid that needed to be brought to these people,” Kerney said.

The so-called delays, such as when residents attempted to cash checks after the disaster, were sometimes out of the hands of both the insurance industry and government.

“One of the things I recall back then, too, was that the banking industry was ill‑prepared. ATMs were available in some instances, but the ATMs often, back in those days, serviced only the bank that provided the ATM, not like today where you can use your ATM card in any ATM machine,” Kerney said. “So people had a hard time cashing those checks and getting their money to make repairs. It wasn’t their fault, it was just something that nobody ever really thought about. So either the bank branch was destroyed, and folks had to go long distances to find another branch, or the ATM machines just wouldn’t allow them to conduct their financial transactions the way we can today.”

Adjuster practices also changed as a result of Hurricane Andrew.

“Back in 1992 in the aftermath of Andrew, and with all of the destruction that went on, for example, in Homestead, again, adjusters were sent into those areas with ‑‑ there was no real concern about the personal well‑being of adjusters. I mean, I wouldn’t say there wasn’t any concern, people were concerned, but there were no methods or no means taken to provide that additional safety, personal safety that adjusters could use. So for example, they went into those areas without cell phones, without means of communicating to the outside world. They went in without water, they went in without food. There were no landmarks, there were no street signs. So adjusters could get into those areas and get lost, and very much find themselves in difficult situations with no way to get out of that situation,” Kerney said.

“I think there are two things to remember about Hurricane Andrew that I think are really important. Number one is the insurance industry learned a lot of lessons, both from the adjusting side and the underwriting side, from the response side, and not only the insurance industry, others, FEMA, the banking industry, the construction industry. Everybody took a lesson out of Andrew, and we’re applying those lessons today, and our responses are getting much, much better,” Kerney said.

“The other important thing, I think, about Andrew to remember is that Andrew made landfall on August 24th, 1992. It was the latest first named storm ever identified. Secondly, it was only the first of six hurricanes that year. So when we look at forecasts, we look back at 2005, we had 25 named storms. Most of the forecasts for the 2012 season are looking at a fairly ‑‑ a little bit above average, but a fairly average hurricane season in terms of the numbers of storms. But what we learned in 1992 is it only takes one, and there may be relatively few in the forecast, but it only takes one, and if that one hits, you know, all bets are off,” said Kerney.

School property scattered about by storm

Mobile park destroyed by the hurricane

Florida residents use humor to cope with Hurricane Andrew’s destruction

Florida homeowner message to insurer

Commercial building brick wall knocked down by winds

Church pews and bibles remain after the hurricane

Church damaged by Hurricane Andrew

Boats tossed about by Hurricane Andrew’s strong winds

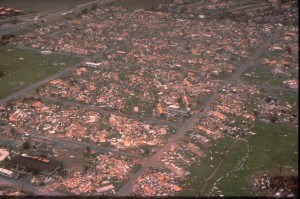

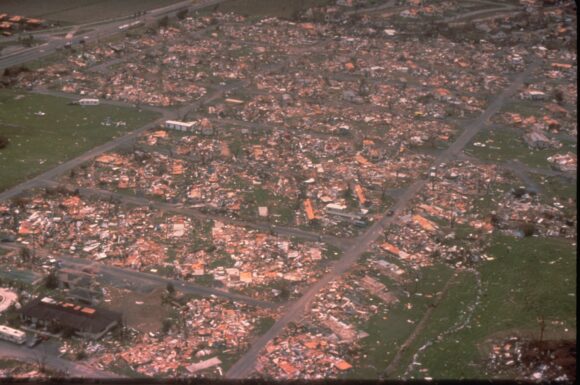

Aerial view of Florida homes damaged by Hurricane Andrew

Aerial view of Hurricane Andrew destruction

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake

Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake  These Five Technologies Increase The Risk of Cyber Claims

These Five Technologies Increase The Risk of Cyber Claims  LA County Told to Pause $4B in Abuse Payouts as DA Probes Fraud Claims

LA County Told to Pause $4B in Abuse Payouts as DA Probes Fraud Claims  Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo

Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo