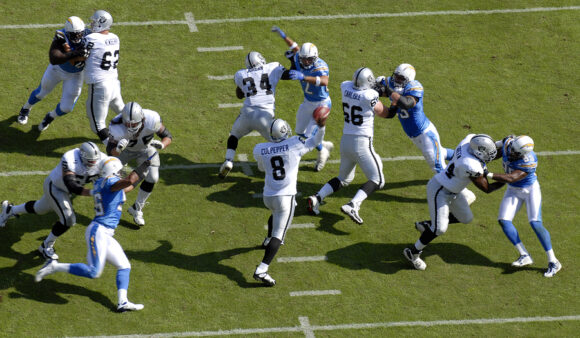

Reports on the danger of head trauma in athletes and soldiers has pervaded the news in recent years. NFL and NHL player deaths have catapulted this problem into the limelight, with stories appearing in the New York Times, NPR, ESPN, 60 Minutes and even television entertainment shows.

Media attention has raced far ahead of the science on this degenerative condition. But scientists are catching on. They have given this disease its own definition—chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

Different from traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or ALS, they say CTE can strike adult and youths alike. Special coverage by Alzforum, a news source on Alzheimer’s and related diseases research, summarizes the status of research in this burgeoning field as researchers take steps to diagnose and treat CTE.

“CTE can start months or years after brain trauma has occurred, either in contact sports, military service, or perhaps even partner violence,” Admiral Regina Benjamin, the U.S. surgeon general, recently told scientists and advocates at the first-ever CTE conference at the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas, Nevada. There, experts came together to define CTE, exchange the latest data, develop a diagnosis, and lay out a research plan.

Some of the newest data comes from boxers and other martial artists who have joined the Professional Fighters Brain Health Study in Las Vegas. The fighters’ history as well as fight statistics are combined with yearly mental tests, brain scans, speech samples, and a blood draw. The aim is similar to studies in Alzheimer’s that have helped identify early signs of disease and track its progression. Scientists want to find out how concussions match up with brain damage and symptoms. Once this study ends, it may generate a tool to help determine when fighters should retire.

Additional information will come from DETECT, a biomarker study of football players, as well as a growing tissue bank of athletes’ and military veterans’ brains. Of 136 tissue donations, 100 brains have been analyzed and 80 had CTE hallmarks. They showed a unique pattern of brain change—expansion in its fluid-filled cavities and shrinkage of its medial temporal lobe—and extraordinary deposits of a toxic form of the tau protein that expand with age. From this data, scientists have begun to outline stages of CTE from beginning to end. It seems some athletes and soldiers who have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s may have had CTE instead.

Additional information will come from DETECT, a biomarker study of football players, as well as a growing tissue bank of athletes’ and military veterans’ brains. Of 136 tissue donations, 100 brains have been analyzed and 80 had CTE hallmarks. They showed a unique pattern of brain change—expansion in its fluid-filled cavities and shrinkage of its medial temporal lobe—and extraordinary deposits of a toxic form of the tau protein that expand with age. From this data, scientists have begun to outline stages of CTE from beginning to end. It seems some athletes and soldiers who have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s may have had CTE instead.

Other research suggests that in CTE, toxic proteins creep from the site of impact to further areas of the brain. Because toxicity moves between cells, not people, researchers refer to the spread as “templating,” not “infectious.” They are developing mouse models to help determine how this spread occurs.

Scientists are also drafting up the best way to diagnose the disease during a person’s life and are pushing for measures to prevent CTE in children, who are more susceptible to developing the condition after head trauma.

Source: The Alzheimer Research Forum

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says

Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says  Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud

Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud  Portugal Rolls Out $2.9 Billion Aid as Deadly Flooding Spreads

Portugal Rolls Out $2.9 Billion Aid as Deadly Flooding Spreads  These Five Technologies Increase The Risk of Cyber Claims

These Five Technologies Increase The Risk of Cyber Claims