A vase can be worth under .50 cents or over $50 million

These days just about every household has some sort of porcelain, whether it’s as a collectible, dinnerware or holiday ornament. And it is one of the most intriguing and often confusing categories in the insurance appraisal business. Given the number of styles, types, and variations in price, unless you’re an expert it’s very difficult to properly appraise.

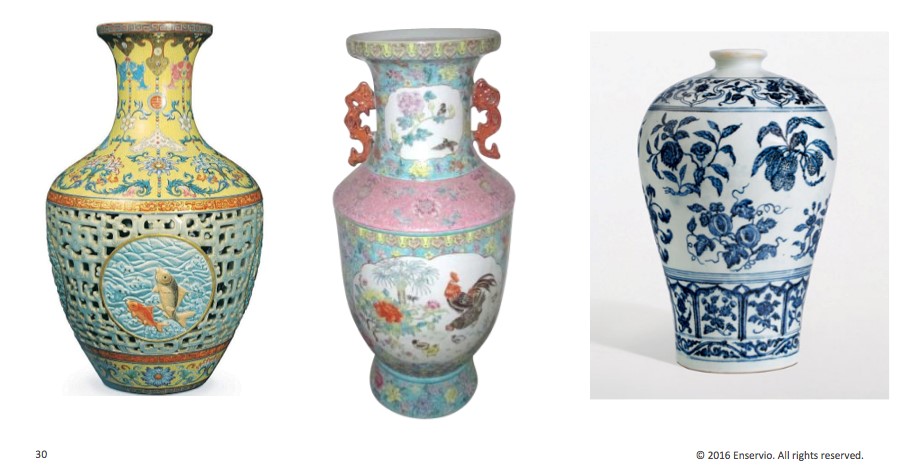

The extreme range in value for Chinese porcelain in particular is seen in these three vases. Can you pick out the one worth $81 million and the one worth $750?

If you guessed the one on the left is the $81 million piece, you got it right. And don’t feel bad if you said the one in the center, because while it appears valuable, the vase is actually from the 20th century and worth $750. The far right Ming vase sold two years ago for $21 million.

Although the difference in price is enormous in the example above, the diamond-in-the-rough phenomenon is not uncommon when dealing with porcelain. Early in my career, I bought a piece at a flea market for $30 that was later sold for $1,800. It was lying among a pile of 50-cent plates.

Given this wide variation in value and porcelain’s relative frequency in insurance claims, it is worth your time to gain at least a cursory knowledge of this contents category.

Making Porcelain

While there are several components to porcelain, true porcelain is comprised principally of two ingredients: kaolin, a smooth workable clay that turns white when fired, and petuntse, which we call feldspar in the west. Porcelain needs to be fired to around 2,500 degrees to create a translucent ceramic, which is impermeable to liquid.

In contrast with the hard-paste porcelain made in China, European makers produced a soft-paste porcelain—a combination of clay and other materials mixed with a finely ground glass called frit. This soft-paste porcelain is, in fact, softer and porous. It’s fired at a lower temperature, somewhere between 2,200-2,300 degrees, and needs to be glazed in order to hold liquid.

A specific type of soft-paste porcelain is called bone china—so named because the clay is mixed with bone ash, sometimes up to 50 percent. It’s most commonly associated with English potteries.

Often it is believed that hard paste is more expensive than soft paste porcelain but this is, in fact, not necessarily true. There are exquisite quality soft paste porcelain pieces that will command significantly higher values than hard paste porcelain. Soft paste porcelain is not as durable as hard paste, which can make high quality pieces comparatively rare.

Important Facts to Record

To determine the place of origin of a piece, check the underside. European-made pieces may have a mark of some sort and Chinese-made works may have what’s called a reign mark—ideally stating the emperor’s reign in which it was made.

Researching porcelain marks can be helpful because it will not only tell you where and by whom a piece was made, it can sometimes provide even a pattern name and when the piece was made. European makers often include a number or letter alongside with their mark on the underside to identify the year it was made. Other European makers would change their mark periodically, thus, giving an idea of the time period of manufacturing.

Note, however, this method of identification, on its own, can be highly unreliable. As you might imagine, marks can be easily forged.

High quality photographs showing the pattern, size, and shape of the work are extremely useful, especially the underside of a piece. If there is a mark, a close-up of the mark showing the details of it, and if that’s not possible then a good description of the mark and the piece is the next best thing.

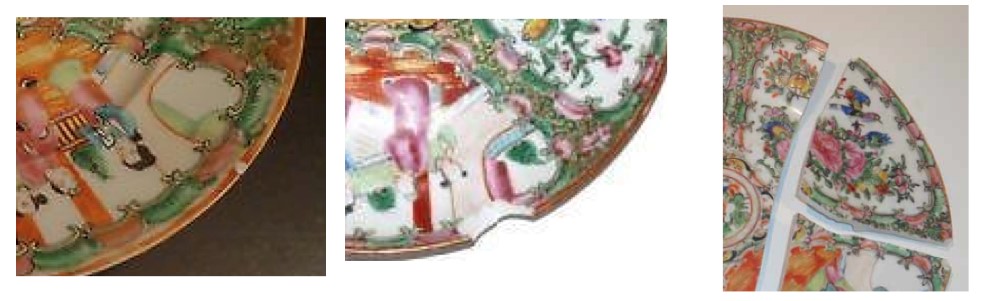

Be sure to record any damage or repairs to the piece as even small chips can have a significant negative effect on the value of an item. In the photos below of 8-10″ porcelain plates, even a small chip, like the one in the image on the left, can drop the value of a piece by 20 to 25 percent. A larger chip, like the one in the center image, can reduce the value by half. And a full break, as on the right, can make the piece worthless.

That said, if the piece is extremely valuable or rare, even a damaged or repaired version can have significant value.

Along with these details it’s important to provide an idea of the size and dimensions of a piece. It’s often difficult to get an idea of how big a piece is in a photograph without a reference. A five, eight, 10, 12-inch plate will essentially look exactly the same in a photograph.

As with most antiques, any kind of documentation can be helpful. A certificate of authenticity (COA), invoice, or receipt showing where the piece was purchased is all useful for proper appraisal. Some dealers are more trustworthy than others and documents from the more highly esteemed dealers have weight.

A good tool to have on hand for on-site porcelain claims is a field guide by J.P. Cushion, “Handbook of Pottery and Porcelain Marks.” It is nearly impossible to determine age and authenticity without outside help and even with expert knowledge it can be quite difficult. That’s partly because porcelain is still being made in Jingdezhen and Europe using the same techniques that have been used for literally centuries.

This is complicated additionally by the fact that porcelain doesn’t age the way wood or textiles do. Porcelain and its glazes are extremely durable and are often kept mainly for display, so there can be little or no wear on a piece.

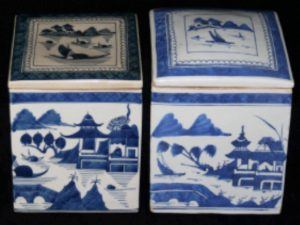

This can be seen in the photo on the right of two Chinese Canton pattern boxes. In this example, one of the pieces is new and the other is old. On first glance it can be difficult to tell the difference—the decoration is essentially the same.

On closer examination however, it is possible to see one is a slightly lighter color than the other. This is deceptive, however, because the lighter color piece (on the right) is actually the antique; notice its contoured lid. Again, proper authentication comes from familiarity with the colors, styles and patterns of the makers alongside reliable documentation.

Over the centuries, porcelain has gone from a collector’s hobby for royalty to one of the most ubiquitous materials in our daily life with values ranging from hundreds of thousands to just a few dollars. Because of this, claims pros needs to be on the lookout both for the rarified piece lost on a bookshelf as well as for a recent copy posing as a priceless antique.

George Somerville Colpitts is a review appraiser for Enservio (www.enservio.com), a provider of contents claim management software, payments solutions, inventory and valuation services for property insurers. With over 20 years of experience in antiques, Colpitts is a former board member & chairman of the Standards Committee of The Antiques Council and former owner of Somerville House Antiques.

George Somerville Colpitts is a review appraiser for Enservio (www.enservio.com), a provider of contents claim management software, payments solutions, inventory and valuation services for property insurers. With over 20 years of experience in antiques, Colpitts is a former board member & chairman of the Standards Committee of The Antiques Council and former owner of Somerville House Antiques.

More tips on evaluating contents claims by Enservio experts:

The Case of the Championship Boxing Belts

Baiting Claims Values on Fishing Gear

Best Practices for Valuing Oriental Rugs

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Why 2026 Is The Tipping Point for The Evolving Role of AI in Law and Claims

Why 2026 Is The Tipping Point for The Evolving Role of AI in Law and Claims  Elon Musk Alone Can’t Explain Tesla’s Owner Exodus

Elon Musk Alone Can’t Explain Tesla’s Owner Exodus  Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo

Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo  Portugal Rolls Out $2.9 Billion Aid as Deadly Flooding Spreads

Portugal Rolls Out $2.9 Billion Aid as Deadly Flooding Spreads