It’s increasingly likely an El Nino will form this year in the equatorial Pacific to roil global weather patterns and threaten natural gas and agricultural markets, the U.S. Climate Prediction Center said in a report.

There’s now a 70 percent chance of El Nino between December and February, according to the report released Thursday. Last month forecasters put the odds at 64 percent.

“We believe the models more the closer we get to winter,” said Michelle L’Heureux, a forecaster at the center in College Park, Maryland. “Just like weather forecasts tend to be better one day out than seven days out, the same thing tends to happen in climate forecasting.”

El Ninos can profoundly impact the planet – particularly financial markets. A powerful one in 2015 hampered cocoa, tea and coffee harvests throughout Asia and Africa and helped choke Singapore with smoke from wildfires. It also ushered in the warmest winter on record in the contiguous U.S., stifling natural gas demand.

Tango Required

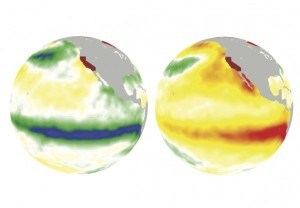

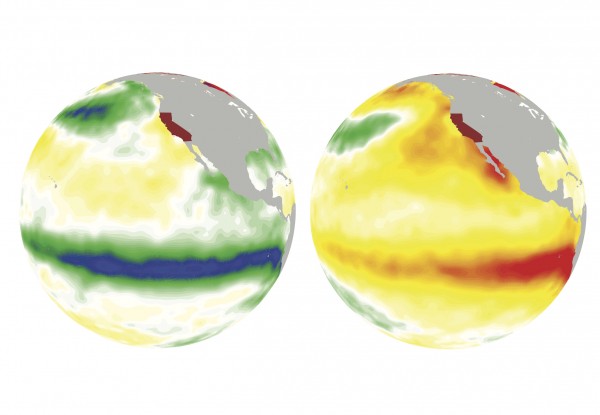

The phenomenon, triggered by warm water in the equatorial Pacific, ushers in weather that varies by region. El Nino winters tend to be cooler and stormier in the southern U.S., rainy in California and warmer in the Pacific Northwest and northern Rocky Mountains. In South America, Brazil is prone to drought. Argentina, meanwhile, may get more rain.

While forecasters have raised their odds, there are few tangible signs the warming trend is actually happening yet. Ocean temperatures rose slightly during June, but they remain less than half a degree Celsius (0.9 Fahrenheit) above the long-term average – which is the threshold needed to indicate an El Nino. Plus, the atmosphere hasn’t shown signs it is reacting to the ocean.

“We like to see a little dancing between the ocean and the atmosphere,” L’Heureux said. “They have to tango.”

The odds for El Nino are greatest from November to January, according to the report. That means it may arrive too late to put the brakes on the Atlantic hurricane season by increasing wind shear in the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico and elsewhere.

Storm Zone

The biggest impediment to Atlantic hurricanes right now is that the ocean between the Caribbean and the coast of Africa is abnormally cool. The area – known as the Main Development Region – is where the most ferocious storms typically form between late August and October.

Research has shown that area of the ocean tends to cool along with the Pacific in the wake of El Nino’s warm-water counterpart – La Nina – and when other patterns such as the North Atlantic Oscillation have a strong positive signal, L’Heureux said. La Nina ended in May.

“If there was something to blame — it might be La Nina,” she said.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud

Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud  Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo

Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo  Founder of Auto Parts Maker Charged With Fraud That Wiped Out Billions

Founder of Auto Parts Maker Charged With Fraud That Wiped Out Billions  China Bans Hidden Car Door Handles in World-First Safety Policy

China Bans Hidden Car Door Handles in World-First Safety Policy