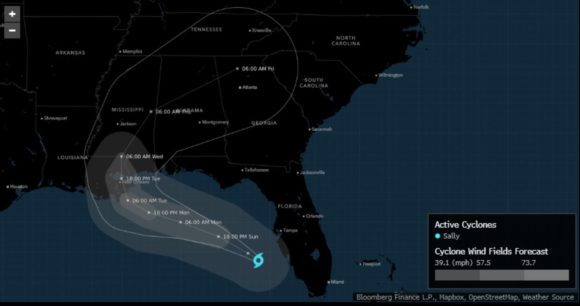

Tropical Storm Sally’s flooding rains are set to reach the U.S. Gulf coast late Monday as the storm grows into a hurricane, making landfall somewhere between New Orleans and Alabama and potentially causing as much as $4 billion in losses and damage.

Sally, which has sparked evacuations on some offshore energy platforms, could reach the coast with winds of 85 miles (137 kilometers) per hour, making it a Category 1 hurricane on the five-step Saffir-Simpson scale. That’s down from earlier forecasts of 100 mph. Landfall is likely to be Tuesday morning.

The U.S. has been pummeled by natural disasters this year, with wildfires devastating the West and storms causing billions of dollars of damage in the East and along the Gulf Coast. Sally is one of 19 named storms in the Atlantic during 2020. That’s the fastest such a tally has been reached in records going back to 1851, said Phil Klotzbach, lead author of Colorado State University’s seasonal hurricane forecast.

“Hurricane conditions are expected by late today within portions of the hurricane warning area from Morgan City, Louisiana, to the Mississippi/Alabama border, including metropolitan New Orleans,” Eric Blake, a U.S. National Hurricane Center forecaster, wrote in his outlook. “Preparations should be rushed to completion in those areas.”

“Hurricane conditions are expected by late today within portions of the hurricane warning area from Morgan City, Louisiana, to the Mississippi/Alabama border, including metropolitan New Orleans,” Eric Blake, a U.S. National Hurricane Center forecaster, wrote in his outlook. “Preparations should be rushed to completion in those areas.”

A larger weather system over the U.S. is making an exact track difficult to forecast, but Sally could be the second hurricane to hit Louisiana since late August. 2020 is now tied for third on the most active seasons, with only 1933 and 2005 producing more storms.

Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards declared an emergency, and New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell issued a similar warning for the city. The storm, which has sparked evacuations on some offshore energy platforms, could raise ocean levels 7 to 11 feet (2-3 meters) at the mouth of the Mississippi River, which could overtop some levees.

The storm could potentially lead to between $2 billion to $4 billion in damage and losses, said Chuck Watson, a disaster modeler with Enki Research. That price tag could rise even more if Sally gets stronger or takes more time moving through the area, or if water overwhelms flood control systems in New Orleans.

Oil Disruption

Sally will sweep the eastern edge of the offshore production area, probably halting oil and natural gas drilling for a short time and adding further disruption to the industry. Hurricanes Marco and Laura, as well as Tropical Storm Cristobal, all halted work across the Gulf this season.

Chevron Corp. said Saturday it’s evacuating workers and shutting in production at its Blind Faith and Petronius platforms. The Louisiana Offshore Oil Port has suspended operations at the Marine Terminal as Tropical Storm Sally approaches in the Gulf of Mexico, according its website.

Mississippi River bar pilots also halted operations Sunday.

Phillips 66 has begun a shutdown of the Alliance refinery, the company said in a statement.

Along with its storm surge, which can vary due to tides and exactly where the storm makes landfall, Sally will bring 8 to 16 inches (20-41 centimeters) of rain across the Gulf Coast from Louisiana to Florida, the hurricane center said. Some areas could get as much as 24 inches and heavy rain is forecast to spread well inland later in the week.

The floods could impact cotton, corn and peanut crops through the region, though widespread damage isn’t expected, said Don Keeney, a meteorologists with commercial forecaster Maxar.

“I don’t think we are going to see any massive damage but there will be some localized flood damage right along the path,” Keeney said. “I don’t think it will have much of an impact on the Delta.”

Seven storms have hit the U.S. in 2020, including Laura, which devastated southwest Louisiana, and Hurricane Isaias, which temporarily knocked out power to millions in the Northeast.

There are currently three named storms in the Atlantic, two tropical depressions and two more potential systems. Hurricane Paulette is battering Bermuda and Tropical Storm Teddy just formed in the far eastern Atlantic. So far Teddy isn’t a threat to land.

“It is definitely a little unusual,” Keeney said. “It is the most active that we have seen in quite a while.”

–With assistance from Kevin Crowley, David Wethe, Robert Tuttle, Dan Murtaugh, Serene Cheongand Christine Buurma.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud

Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud  Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake

Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake  Hackers Hit Sensitive Targets in 37 Nations in Spying Plot

Hackers Hit Sensitive Targets in 37 Nations in Spying Plot  Founder of Auto Parts Maker Charged With Fraud That Wiped Out Billions

Founder of Auto Parts Maker Charged With Fraud That Wiped Out Billions