On a typical weekday before the coronavirus pandemic, tens of thousands of commuters passed through the Journal Square train station in Jersey City on their way to and from New York City. The station is one of the busiest on the Port Authority Trans-Hudson, or PATH, train line that runs under the river between New York and New Jersey. Last spring, during the height of the lockdown, ridership through Journal Square plummeted to less than 3,000 people per day and has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels.Erin Vinson, a 34-year-old who works as a training coordinator at a safety school for construction workers, is one of those still using the station. On weekday mornings, Vinson rides her electric scooter about a mile from her apartment to Journal Square and then takes the PATH to downtown Manhattan. Her scooter stays behind in Jersey City, locked in a shelter on the sidewalk outside the station. Each morning, Vinson swipes a card to unlock the door to the shelter — a perforated aluminum hut, wrapped in advertising for a nearby burger shop and topped with potted plants — and leaves her scooter alongside the few bikes also parked inside. “It’s a brilliant idea,” Vinson says of the system. “Everything about it is easy.” The parking hut is operated by a startup called Oonee (pronounced ooh-nee, after the Japanese word for sea urchin), which builds modular parking shelters, called pods, for bikes and scooters. Shabazz Stuart, a 31-year-old Brooklyn native, came up with the idea for Oonee in 2015, while working for a business improvement district in the borough. He was commuting by bicycle — about a two-and-half-mile trip from his apartment in Crown Heights to downtown — and had his bike stolen three times in a span of five years. After the third, Stuart decided there had to be a better way. So he and co-founder J. Manuel Mansylla began working on designs for a modular parking pod that wouldn’t create an eyesore on a city sidewalk. “We need to give people secure bike parking,” Stuart says, “and not just one or two spots.” For now the Oonee pod in Jersey City is one of two; the other sits at the Atlantic Terminal in Brooklyn near the Barclays Center arena. On Thursday the company announced plans to install two mini pods in New York City this spring. Swedish scooter sharing company Voi, one of the bidders currently seeking a contract to operate scooters in New York, has agreed to pay $25,000 to fund the two installations. Oonee plans to ask riders to help decide the location for these initial curbside pods, each about 7 feet long and able to hold as many as seven bikes. The company’s aim is to build a dispersed network of hundreds of pods across the city, with the larger walk-in versions set in high-traffic areas and the smaller lockboxes dotting residential blocks.

“We need to give people secure bike parking,” Stuart says, “and not just one or two spots.” For now the Oonee pod in Jersey City is one of two; the other sits at the Atlantic Terminal in Brooklyn near the Barclays Center arena. On Thursday the company announced plans to install two mini pods in New York City this spring. Swedish scooter sharing company Voi, one of the bidders currently seeking a contract to operate scooters in New York, has agreed to pay $25,000 to fund the two installations. Oonee plans to ask riders to help decide the location for these initial curbside pods, each about 7 feet long and able to hold as many as seven bikes. The company’s aim is to build a dispersed network of hundreds of pods across the city, with the larger walk-in versions set in high-traffic areas and the smaller lockboxes dotting residential blocks.

“In New York we have more than 3 million free curbside parking spaces,” Stuart says. “Do we want to provide people with access to bike and scooter parking? Or do we want to preserve the space for cars only?”

In the long term, Oonee aims to bring its pods to other cities and, once they attract enough users, to offer a larger set of services through the company’s app. If riders, for instance, pop a tire on the way to work, Stuart wants them to be able to use the app to arrange for a mechanic to come to the pod and fix the flat the same day. He also plans for users to be able to buy bikes and scooters, as well as accessories and insurance, through the app.

Oonee would contract with third-party providers for these services and take commissions of about 15% on the transactions, making the company, Stuart says, into a “one-stop shop, right on your phone, for everything related to bike or scooter ownership.” Whereas many European cities, including London and Paris, are building out comprehensive bike-parking networks through government spending, Oonee is attempting to build one through an e-commerce business model.

In the U.S., bike parking is a problem riders are mostly left to deal with on their own, with sporadic support from employers, property managers, universities, and local governments. If you are lucky, your office or apartment building might have a secure bike room; your college might install lockers or racks; or your city might be one of those with bike parking stations near commuter trains. But even for riders blessed with adequate parking where they live and work, trips to the grocery store, gym, or coffee shop are a crapshoot.

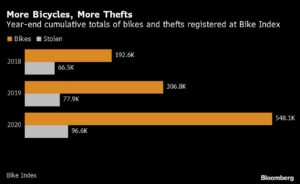

As bike sales have surged in the U.S. since the coronavirus outbreak, thefts, inevitably, have followed; but it’s hard to say if thieves have kept pace with buyers. Nationwide, last year, riders added 241,356 bikes to the Bike Index, a nonprofit registry service, bringing the total to more than a half-million. Of the more than 240,000 registered last year, 16,022 were reported stolen. In 2019, riders registered 114,215 bikes, with 10,288 of them reported stolen. So though thefts have risen by almost 56%, registrations are up 111%.

These numbers capture only a fraction of the problem. Project 529, another bike-registration service, estimates that more than 1.7 million bikes are stolen in the U.S. each year and that only 15% to 20% of those thefts get reported to police. The company, co-founded by former Microsoft executive J. Allard in 2013, uses data from its own registry of 1.8 million bikes in North America — along with the sparse collection of academic literature on the subject and input from city police departments — to reach these figures, which, Allard acknowledges, are educated guesses. Many bike thefts, he notes, are part of burglaries from home garages, and apartment complexes that don’t always show up in police tallies.

Whatever the case, bike theft, by most accounts, remains rampant and largely unchecked. The rising popularity of e-bikes, which often cost thousands of dollars, has only made the problem worse. At Bike Index, which asks users to enter an estimated value for their bikes, the average value of stolen bikes is about $1,500. “It’s not uncommon to see $5,000 e-bikes in here,” says the service’s co-founder Bryan Hance.

Oonee’s first public pod was installed in downtown Manhattan in the fall of 2018 and closed less than a year later after the company and the New York City Department of Transportation could not agree on guidelines for advertising on the structure. “We had to take that one down after 10 months because we were operating basically a charity,” Stuart says. “We had $900 in the bank.” Relationships with the realty company where the Brooklyn pod is located and with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, landlord at the Jersey City train station, have gone better. In an emailed statement the Port Authority said it is proud of Oonee’s “innovative solution” at Journal Square and looks forward to continuing to work with the company.

Oonee’s walk-in pods cost about $80,000 to build and are free to anyone who signs up for the app and provides proof of identity. Vinson in Jersey City, who signed up for the service last summer after purchasing her scooter, says she was surprised there was no charge. “I expected to pay $20 or $30 a month.” While Stuart says Oonee may someday charge fees for bikes and scooters left in pods for more than a day two, he is committed to running a low-cost service: “If you are going to occupy public space, having an egalitarian structure is very important.”

Oonee gets its revenue, which it shares with the property owners, from the advertising space on the shelters. The two pods already in operation, Stuart says, bring in more than enough money to cover their upkeep. Most of the smaller lockboxes, he says, will not have advertising, though those placed in commercial zones may have digital screens. Revenue from the ad-bearing pods, he anticipates, will be enough to offset the cost of the others.

Each walk-in pod comes equipped with a security camera. Oonee insures the bikes and scooters inside against theft and, if one is stolen, passes along the payout to its owner. Riders use their own locks to secure their bikes to racks inside. So far, Stuart says, riders have parked in Oonee’s pods more than 60,000 times with only a single theft, which came after someone used a fake ID to gain access in Brooklyn. Vinson in Jersey City has used the pod hundreds of times without incident. She’s eager, she says, for Oonee to expand its services. “My scooter is due for a service, and finding someone who actually does that around Jersey city is not an easy thing,” she says. “To be able to book an appointment to have someone come and do it in the pod while I’m at work would be sensational.”

In January, Oonee joined the Brooklyn-based start-up accelerator Urban-X, which provides $100,000 in funding and access to outside experts in design and product development. Stuart says he’s using that support to prepare the company for more fundraising later this year. He’s looking to raise $2 million to $3 million to expand operations and begin building the e-commerce platform he anticipates can turn his humble three-person operation into a multibillion-dollar company.

One of the biggest difficulties, Stuart says, is that many investors are not accustomed to hearing pitches from people like him: a black man from a single parent household who never had the kinds of friends and family who might participate in a “friends and family” fundraising round. While black people represent 13 percent of the U.S. population, less than one percent of founders who receive venture capital are black. “When I go to investors and do this as a black man,” says Stuart, “I think there’s some reticence.”

“I don’t know if this company is the answer,” says Reilly Brennan, a founding partner at the San Francisco venture capital fund Trucks, which passed on an opportunity to invest in Oonee in 2018, “but one of the things about transportation that I’m always obsessed with is that it’s the real estate and parking aspects that make these systems work.” So far, Brennan says, nobody has figured out how to make bike parking into an amenity that people will pay for.

From a purely economic point of view, says Christopher Cherry, a professor in the department of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, bike parking facilities often don’t add up: The value of the property stolen each year is less than the cost to build and maintain the shelter. “I’d rather have ubiquitous racks everywhere than really nice, high-tech racks in a couple of places,” Cherry says. A few years ago he helped his university revamp its bike parking by putting racks near the front doors of most buildings. Many riders, he says, had refused to go out of their way to use racks, instead locking their bikes to the nearest pole or tree.

If Oonee’s pods are ever to serve more than a handful of commuters, in other words, they will have to be dotted all across any city where the company operates. “The average range is two or three blocks before people say, ‘Oh, it’s not worth it,'” Stuart says. “So we need to have hundreds, if not thousands, of smaller facilities on city streets.” Reaching that scale will require working with hundreds of property developers and local governments, building and maintaining thousands of pods, and coordinating with a wide array of local service providers. “It’s a radical vision,” Stuart says. “It’s an ambitious vision. I don’t deny that. But those are the ideas that are worth doing, in my opinion.”

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

US Will Test Infant Formula to See If Botulism Is Wider Risk

US Will Test Infant Formula to See If Botulism Is Wider Risk  Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says

Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says  Founder of Auto Parts Maker Charged With Fraud That Wiped Out Billions

Founder of Auto Parts Maker Charged With Fraud That Wiped Out Billions  Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case