Waseem Tarabishi insists that employees at his San Diego-area collision repair shop take the online classes they need to maintain their technical certifications while on the clock so he can make sure they are paying attention.

After buying CollisionTech in El Cajon three years ago from owners who “didn’t know what they were doing,” he invested $35,000 in a TruScan Live Mapping System that can detect structural damage that otherwise might go unnoticed. Regular software updates to the scanner cost $1,500 a year.

He also owns a $2,500 scanner for vehicle electronic systems. Regular software updates cost $1,100 annually. He pays for memberships that provide regular updates to collision repair manuals produced by auto manufacturers.

Tarabishi’s effort to keep up with technology has earned him a five-star customer-satisfaction rating on Yelp and a Gold Class designation by the Inter-Industry Conference on Auto Collision Repair. He said the I-CAR certification is practically mandatory if he wants insurers to send business his way, but it’s not always a pleasure to work with them.

“The industry is controlled by the insurance carriers,” he said. “I call them mafia.”

Tarabishi said his dim view is shaped by claims adjusters who push to finish jobs quickly instead of taking the time to do it right. He said carriers seem unconcerned about repair work that leaves hidden damage behind, endangering the safety of their customers.

“They are counting on your stupidity,” he said. “What you don’t know saves them money.”

Tarabishi is one of many experts who believes that technical acumen and strict adherence to manufacturers’ repair specifications are imperative for today’s collision repair industry. Auto manufacturers are using new materials to reduce vehicle weight, adding sophisticated safety systems and forsaking the internal combustion engine for all-electric propulsion. Technicians who once relied mostly on welding torches and ball-peen hammers now need the help of advanced scanning and diagnosis equipment, along with online access to manufacturers’ updated repair procedures.

Do the right thing

Efforts to control costs and reduce claim cycle times creates tension between insurers and collision repair professionals. The use of smart-phone apps that create photo-based preliminary repair estimates may add to that friction by fomenting overly optimistic expectations.

“How do you know what’s under there?” asks Frank Terlap, an inventor who co-founded a company that makes calibration equipment for automotive safety systems and author of a book titled Auto Industry Disruption.

According to Mitchell, a San Diego-based claims administrator and data analytics provider, 93% of vehicles on US roads are now equipped with advanced driver assistance systems, known in the industry as ADAS. Those systems generally require recalibration after a crash.

Terlap said industry data shows that collision repair shops aren’t performing nearly as many calibrations as they should. Mitchell reported last September that only 8.5% of claims for repair to vehicles in the 2018 to 2020 model years generated the line item that indicates an ADAS calibration was conducted. Terlap said the vast majority of late model cars require a calibration after a collision, yet the insurance industry has no measures in place that ensure all of the work that should be done after a collision is done.

Perhaps for good reason. Terlap said ADAS calibrations can add $300 to $2,000 to the cost of repair.

Terlap said much of the tension between insurers and collision repairers dates to the creation of direct repair programs, where work done at body shops that belong to an insurer’s network. He said insurers tell the repair shops what they will pay for and what they won’t, so work that is required according to the manufacturer’s specifications might not get done if it’s not included in the insurer’s DRP agreement.

Manufacturers, on the other hand, are keenly interested in proper repair procedures. They know from market research that customers who are unhappy after a collision repair are much more likely to replace their vehicle with another brand, he said. That’s why some manufacturers are forming partnerships with insurers and steering business to repair shops that are “certified” to work on their car brands.

“The industry wants to do the right thing. It’s just catching up,” Terlap said. “The problem, though, is the cars are changing so fast.”

Mitch Becker, director of training for Pro-Tech Automotive Solutions, said many ADAS sensors are attached to vehicle windshields. Becker said 14 million windshields are replaced annually in the US. Because of ADAS, what used to be a relatively simple repair job now takes much longer.

“The average windshield claim in the United States has more than doubled,” Becker said.

Becker said the addition of ADAS systems into windshield design requires an exact calibration that can be done only inside a body shop, at least if the manufacturer’s specifications are followed. Becker said imagine an ADAS sensor emits a laser beam aimed at a target the size of a credit card. If the angle of the laser is shifted one degree, at a distance of 150 meters that beam will be aimed into the adjacent traffic lane, pointing into oncoming traffic.

Becker said he knows of technicians who think they can skip the calibration process by leaving the ADAS equipment connected when the windshield is removed. “Nothing could be further from the truth,” he said.

Instruments cannot be properly calibrated without a test drive, he said. ADAS sensors are aimed at specific targets — the lane marker at the edge of the road or the vehicle directly in front. Highway travel is necessary to ensure they are calibrated. Often, the weather doesn’t cooperate. For example, snow may obscure the traffic lanes that serve as cues for lane-departure warnings.

“We’ve had cars that we had to drive 70 miles to get the system calibrated again,” Becker said.

Even as the job of auto body repair became more technical, vocational schools are dropping training programs because it is too expensive to keep up with technology, Becker said. The result is a shortage of a skilled labor, which explains why Becker’s employer operates its own school. Even experienced technicians need continuing education as technology advances.

“You’re never done with school,” he said.

Becker said autobody repair technicians are typically expected to bring their own tools to the job, and the cost of tools can be a barrier to entry in the field. He said the time it takes to learn the job can also be daunting. Becker said it takes at least two years to learn the trade.

“The companies are battling over the people who are in this industry because there are not enough,” he said.

Frequency down, severity up

Industry experts confirm Becker’s observations.

Susanna Gotsch, an auto insurance analyst for CCC Information Services, said in a Jan. 11 report that 50% of all vehicles manufactured from 2017 to 2020 have automatic emergency braking systems that require “challenging diagnostics.”

Gotsch said ADAS is contributing to a long-term trend of declining claims. She said in 2019, CCC saw a 0.2% decline in non-comprehensive claim counts, which includes both repairable and total losses. Last year those claims were down 24%, largely because of remote work assignments and social distancing measures related to COVID-19.

At the same time, ADAS systems are increasing the cost of repairable claims. Gotsch said before the pandemic, claims costs were increasing by about 3% to 4% annually. She said a combination of more severe accidents and more vehicle technology spurred claims costs to rise by 5% to 6% in 2020.

“The new technologies like ADAS, lightweight materials, additional costs for things like vehicle scan and calibration are largely behind the increase in repair costs,” she said in an email.

Higher used car costs are also driving claim costs. Gotsch said CCC expects total loss claims to jump from 5-6% for the full year 2020, although much larger increases were seen during the second half the year after the Bureau of Labor Statistics increased the consumer price index for used vehicles by 11 points.

Because today’s cars last longer and vehicles are older, on average, than they used to be, the full impact of ADAS on claim frequency has not been fully felt. Grotsch said fewer than 20% of registered vehicles are equipped with the ADAS systems that have been shown to have the most efficacy in reducing claim counts, such as blind-spot monitoring, front and rear automatic emergency braking and forward collision warning.

Gotsch said the growing use of technology in vehicles forces repair shops to invest in tools and training that are specific to individual manufacturers. She said repairers are having to make decisions about where they should specialize.

Insurers pay for 89% of collision repair costs, according to CCC. Increasingly, repairs are being done through direct repair programs. Gotsch said DRPs made up 41.9% of repairable appraisals during the first 10 months of 2020, up from 37.4% in 2018.

An increasing number of direct repair program appraisals are conducted by national multi-shop organizations (MSOs) and fewer are being conducted by independent shops. Gotsch said MSOs conducted 37.6% of appraisals in 2020, up from 5.8% in 2000. The share of appraisals conducted by independent shops declined to 51.3% from 85.3% during that period.

“The large MSO’s, franchises, and dealership groups in many cases are growing their number of locations and the markets they serve, and subsequently are seeing their share of the market grow,” she said.

All-electric future

General Motors is betting that the growing popularity of electric vehicles will not be a fad. On Jan. 28, America’s largest car builder announced that it plans to become carbon neutral by 2040 and eliminate tailpipe emissions from new light-duty vehicles by 2035.

“Our plans are an all-electric future and we’re moving very aggressively on that front,” said John Eck, collision manager for General Motors, during a January webinar sponsored by the Collision Industry Electronic Commerce Association.

That’s a long voyage. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, 1.44 million plug-in electric vehicles were sold in the US from 2010 through 2019. Even if all of those vehicles are still on the road, that represents a small fraction of the 276 million registered vehicles in the US.

But the technology has been advancing rapidly and electric vehicles are expected to overtake the internal combustion engine as the primary method of propulsion in 10 to 20 years.

In a January 2020 report, Boston Consulting Group projected that electric vehicles will take a third of the global automobile market in 2025 and 51% by 2030. That projection includes plug-in hybrid vehicles with internal combustion engines, but BCG expects hybrids to fade in market share as battery-electric vehicles gain dominance.

Globally, passenger electric vehicle sales jumped from 450,000 in 2015 to 2.1 million in 2019, BloombergNEF said in a report last May. The COVID-19 pandemic slowed the sale of electric vehicles in 2020 along with all other cars, but BloombergNEF said the industry will recover along with the economy will make up 58% of new passenger car sales by 2040.

The growing use plug-in electric vehicles powered by batteries is adding another layer of complexity to collision repairs.

Batteries packs large enough to power cars are heavier than internal combustion engines, so manufacturers shave weight by building auto bodies out of lightweight materials metals, such as ultra-high-strength steel and carbon fibers, that require different kinds of tools.

The batteries themselves present challenges. A collision can set off a chemical reaction, called a thermal runaway, among the battery cells that will continue burning or reignite after being doused with water, according to report last month by the National Transportation Safety Board. Repair technicians who break into a wrecked electric car can receive a fatal shock by the high-voltage energy stored in the batteries.

An article published in December by Mitchell said parts on electric vehicles such as hoods and fenders are replaced, rather than repaired, more often than with gasoline-burning cars. Electric vehicles often need to be scanned more often and exhibit more flaws when they are scanned, according to the report by Mitchell Director of Claims Performance Ryan Mandell.

Mandell said estimates for electric vehicle collision repairs include a diagnostic scan 49.6% of the time, compared to 38.6% for conventional vehicles. While late-model gasoline cars are scanned almost as frequently as electric, the scans that are conducted reveal more faults with electric vehicles. Mandell said electric vehicles produced an average 12.6 fault codes per scan, compared to 8.5 for internal-combustion engine vehicles.

Electric vehicle manufacturers use more lightweight materials such as aluminum, ultra-high strength steel composites and carbon fiber when building cars. Mitchell data shows parts made from such materials are more likely to require replacement rather than repair. Quarter panels, for example, are repaired 83.2% of the time for internal-combustion vehicles, but 74.6% of the time for electric cars.

Repairs also take longer. Specifically, Mitchell found that electric vehicle collision repairs required 27.4 hours of labor compared to 23.3 hours for internal-combustion cars.

“EVs truly are a different breed—one that comes with a unique set of requirements and exemplifies the changes in vehicle complexity seen over the past decade,” Mandell wrote.

Marcial Nuno, the manager of CollisionTech in El Cajon, said he will probably be retired by the time electric cars take over roadways.

He entered the trade in the 1980’s after two semesters of training. Nowadays, he said, technicians go to school for two or three years.

No matter. Nuno said like everything else, on-the-job experience is what matters. “You’ve heard about 10,000 hours?” he asked.

Nuno has that much and more. After learning the repair trade, he worked 11 years as an appraiser for insurance carriers. In fact, that experience landed him his job managing Tarabishi’s shop.

Nuno said he spends a couple of hours every other week or so taking online classes to keep up with is I-CAR certifications. He said the auto-collision trade has changed a lot over the years, but one thing remains the same.

“You have to keep learning,” he said. “It’s only upgrading your knowledge.”

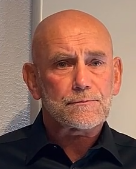

About the photo: Waseem Tarashibi points out an ADAS sensor on the front bumper of a BMW at his shop, CollisionTech, in El Cajon, Calif. He said such details can be easily overlooked if collision repairers don’t follow manufacturers’ protocols. Photo by Jim Sams.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

China Bans Hidden Car Door Handles in World-First Safety Policy

China Bans Hidden Car Door Handles in World-First Safety Policy  Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says

Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says  US Will Test Infant Formula to See If Botulism Is Wider Risk

US Will Test Infant Formula to See If Botulism Is Wider Risk  FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings

FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings