Janice Shell likes to sniff out fraud. An art historian by training, she once spent her days digging through Renaissance archives in Italy. Now 74, retired and living in suburban Philadelphia, she pores over financial filings instead. She hunts for sketchy penny stocks, then flags them in tart commentaries on message boards such as Investorshub.com. Shell has been remarkably prescient. In several cases, the US Securities and Exchange Commission later sanctioned companies she’d called out—and for the same reasons.

In 2011, on TheStreetSweeper.com, Shell questioned how Miller Energy Resources Inc., an oil and natural gas driller in Tennessee, valued its properties. “This Hot ‘Alaska’ Stock May Be About to Melt,” the headline read. Four years later the company paid more than $5 million to settle SEC allegations that it overstated the value of its Alaska oil and gas reserves. Miller Energy, which neither admitted nor denied the claims, ultimately filed for bankruptcy.

The SEC runs a whistleblower program that would seem perfect for Shell. If investigators bring a successful case based on information sent their way, the informant can keep 10% to 30% of any money recovered as a reward. Over the years, Shell figures she’s sent in a dozen tips. But she stopped about seven years ago, because she never heard back. “It’s such a nuisance when you know they aren’t going to get to it this year—and maybe not ever,” she says.

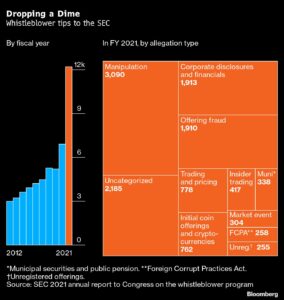

Her gripe is typical of those who alert the SEC. They include corporate insiders, amateur stock sleuths and professional investors, including short sellers who profit from the declines in share prices. (Shell says she didn’t short Miller Energy but has bet against other shares, though not recently.) Her lament reflects a reality of the 11-year-old whistleblower program: Out of 60,000 tips sent its way, fewer than 300 have resulted in awards.

The SEC, which won’t say how many of these leads have merit, insists it reviews each one. But even when the information pans out, investigations and court proceedings can drag on for years. Whistleblowers remain in the dark about whether they’re in line for awards, and why or why not. The program operates in almost complete secrecy. Tipsters have waited as long as a decade to collect money. About 12,000 tips flooded the whistleblower program last year, triple the number six years before. “I wish we had more resources,” SEC Chair Gary Gensler says. “It’s been an important piece of sourcing data and information” that can help the agency become, “within our limited resources, a better cop on the beat.”

Senators Elizabeth Warren, a Massachusetts Democrat, and Chuck Grassley, an Iowa Republican, championed the whistleblower system, which Congress created in 2010 as part of the Dodd-Frank financial reform law. The Tips, Complaints and Referrals Program addressed a sad chapter for the SEC: For almost a decade, the agency ignored frequent warnings from an outside analyst, Harry Markopolos, about Bernie Madoff’s $64.8 billion Ponzi scheme. Since then, the program has recouped $5.6 billion for financial fraud victims and awarded $1.4 billion, or 25%, to whistleblowers.

New York attorney Bill Singer, who won a $1.6 million award for a client in 2016, says the program needs revamping. He suggests letting informants file lawsuits in federal court on behalf of taxpayers, also with the prospect of keeping a share of any recoveries. That’s how the US Department of Justice whistleblower system works under the False Claims Act, which was enacted during the Civil War to fight defense contractor fraud. Federal prosecutors later have the option to intervene, though private citizens can and do pursue alleged fraud on their own.

Letting whistleblowers file complaints in court would add credibility to the program and broaden participation, Singer and other attorneys who’ve worked with the SEC and Justice Department say. At the SEC, more than $420 million—almost one-third of all awards—has gone to clients of only three law firms who employ former senior SEC attorneys, including one who created the whistleblower program and another who led it for five years, Bloomberg Law reported in July. The agency said it doesn’t give preferred treatment to its former staff.

“There is such a quick fix out there, and that’s to use whistleblowers as an adjunct staff of thousands of men and women out there finding this fraud every day,” says Singer, a former official with the National Association of Securities Dealers, now known as the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. “It’s been a very successful program, but it’s more than 10 years old now, and it’s grown to the point where it needs legislation to deal with the reality that most tips are never getting any response.”

Michael Goode, who runs a penny stock site called GoodTrades.com, says he’d filed many tips with the agency and heard nothing. “I don’t like scams, which is funny, because that’s how I make a lot of my money,” says Goode, who often shorts Chinese shares. “I hate the thought that a whole group of people is being taken advantage of and losing their money, so the least I can do is try to let the SEC and investors know.”

Michael Goode, who runs a penny stock site called GoodTrades.com, says he’d filed many tips with the agency and heard nothing. “I don’t like scams, which is funny, because that’s how I make a lot of my money,” says Goode, who often shorts Chinese shares. “I hate the thought that a whole group of people is being taken advantage of and losing their money, so the least I can do is try to let the SEC and investors know.”

Others gathering intelligence for the government have a more personal connection; they consider themselves victims of fraud. In Dallas, John Barr says he and his family bought $1 million in life settlements, or viaticals, through Life Partners Holdings Inc., a company in Waco, Texas. The unusual securities let investors buy life insurance policies from holders, pick up premium payments and then collect when the insured person dies. They’re a bet that the cost of buying and maintaining the contracts will be lower than the ultimate payout; they can bring a windfall if the insured dies relatively soon or cause a loss if the person lives unexpectedly long.

Barr later suspected that the investments weren’t all they’d initially seemed; a cancer victim whose policy he’d bought was actually much healthier than he expected and was even seen enjoying an excursion in Africa. Barr alerted the SEC. In 2012 the agency filed a civil complaint alleging that Life Partners and three of its senior executives misled investors about the life expectancies of those insured under the policies. The company fought the allegations in court. In 2014 a federal judge imposed $46.8 million in fines, affirming a jury verdict that found the company had misled investors. Life Partners filed for bankruptcy protection, and the case dragged on for years.

The situation demonstrates the long road for whistleblowers, even when the SEC finds merit in their information. Barr says he’s spent more than five years working with SEC staff and offering testimony in court, while facing personal attacks from the company. Although the SEC called him as a key witness—and he’s filed formally for an award—Barr has yet to get one, and it’s unclear if he ever will. “It was difficult going through that,” he says. “And it’s been very hard now just waiting all these years to get this resolved.”

A fortunate few have made out quite well. Yolanda Holtzee, a 66-year-old retired US Army lieutenant who lives near Seattle, says she’s won four whistleblower awards totaling about $1.5 million. In the largest, she told the SEC about the activities of Canadian stock promoter John Babikian, known as the Wolf of Montreal. “It just bothers me to see people prey on those who just aren’t as fortunate,” Holtzee says. In 2014, Babikian, without admitting or denying responsibility, agreed to pay $3.7 million in fines and disgorgement to settle SEC allegations that he used sites such as AwesomePennyStocks.com to recommend shares of a thinly traded mining company that he was secretly dumping through a Swiss bank. For her help in the case, Holtzee collected $1.1 million.

In another case, she researched the volatile trading of two penny stocks, Cascadia Investments Inc. and Green Oasis Inc. She traced their gyrations to a stock promoter in Connecticut, Jerry Williams, who ran seminars where he recommended the shares. In 2014 the SEC ordered Williams to pay $9.6 million in disgorgement and penalties. The SEC alleged he secretly sold shares he touted, which Williams neither admitted nor denied. Holtzee was in line for a windfall, a third of the money. Unfortunately, the SEC didn’t recover any. In an outcome dreaded by whistleblowers, she ended up getting 30% … of nothing.

–With assistance from Lydia Beyoud.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo

Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo  Hackers Hit Sensitive Targets in 37 Nations in Spying Plot

Hackers Hit Sensitive Targets in 37 Nations in Spying Plot  One out of 10 Cars Sold in Europe Is Now Made by a Chinese Brand

One out of 10 Cars Sold in Europe Is Now Made by a Chinese Brand  Uber Jury Awards $8.5 Million Damages in Sexual Assault Case

Uber Jury Awards $8.5 Million Damages in Sexual Assault Case