Is it possible to predict exactly where the wind will blow? How about where it will blow 30 years from now?

The First Street Foundation, a nonprofit that works to define and communicate risks posed by climate change, says it has developed a model to assess “hyper-local climate wind risk” in the US now and into the future, in a report released Monday.

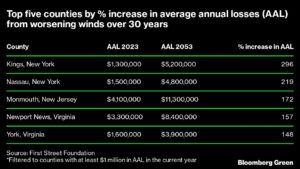

First Street estimates that 13.4 million US properties that aren’t currently vulnerable to tropical cyclones likely will be in 30 years’ time. Annual damages from high winds will rise by $1.5 billion to nearly $20 billion in 2053, according to the report, with damages rising the most — 87% — in the Northeast US. The Mid-Atlantic region will see the largest increase in maximum wind speeds, with maximum wind gusts in some places blowing up to 37 miles per hour faster.

The group based its model on pioneering peer-reviewed research by Kerry Emanuel, an atmospheric scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Emanuel projected in 2006 that climate change was likely to increase storms’ intensity and might shift their geography.

Working with Emanuel on the new study, researchers simulated 50,000-plus storm tracks based on warming climate conditions. In the future, they determined, more storms in the US would likely reach a strength of Category 3 or higher. Because of changes in weather patterns due to climate change, these storms would also be able to sustain themselves long enough to travel north farther up the East Coast. Buildings in areas that haven’t weathered such severe storms in the past weren’t necessarily built to withstand them.

Working with Emanuel on the new study, researchers simulated 50,000-plus storm tracks based on warming climate conditions. In the future, they determined, more storms in the US would likely reach a strength of Category 3 or higher. Because of changes in weather patterns due to climate change, these storms would also be able to sustain themselves long enough to travel north farther up the East Coast. Buildings in areas that haven’t weathered such severe storms in the past weren’t necessarily built to withstand them.

Study researchers estimated the maximum speed of such storms’ 3-second gusts of high wind, which cause the majority of severe wind damage. They used models provided by Arup, an engineering firm, to evaluate damages such gusts would inflict on dozens of different property types. Combining all these data, they calculated the likelihood that any property in the contiguous US would experience financial impacts from a cyclone, today and 30 years in the future.

Although storms are moving north, Florida now accounts for over 70% of the nation’s total wind risk and will continue to bear most of the losses. After 1992’s Hurricane Andrew, Florida adopted some of the toughest building codes related to wind in the nation. However, these apply only to construction from the mid-1990s on, and frequent hits to the state will work against the stringent codes.

As it has done previously for its risk models for flood, wildfires and heat, First Street will release a wind-risk calculator that can look at individual properties. Insurance firms have sophisticated capabilities for modeling wind damage, but their modeling is proprietary; First Street says its tools fill a market gap by informing owners of their vulnerabilities and how they are growing due to climate change.

“Compared to the historic location and severity of tropical cyclones, this next generation of hurricane strength will bring unavoidable financial impacts and devastation that have not yet been priced into the market,” said Matthew Eby, First Street’s chief executive officer.

However, in order to project risks into the future, First Street combines three different models: a hazard model, an exposure model and a durability model. Each time one model is combined with another it adds another degree of uncertainty to the outcome, said Mona Hemmati, a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University’s Climate School who does similar modeling.

First Street doesn’t routinely publish its error rates, which is unusual in climate science. The study’s lead researcher Ed Kearns said the estimated increase of 13.4 million homes might be off by up to 2.5 million, plus or minus.

“This is very innovative research,” Hemmati said, “but the uncertainty really needs to be communicated better to the public.”

Top photo: A destroyed house following Hurricane Ian in Fort Myers Beach, Florida, US, on Tuesday, Oct. 4, 2022. Florida cities looking to rebuild from the devastation of Hurricane Ian will be financing their efforts during the worst environment for municipal borrowing in more than a decade.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says

Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says  Hackers Hit Sensitive Targets in 37 Nations in Spying Plot

Hackers Hit Sensitive Targets in 37 Nations in Spying Plot  Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case  UBS Top Executives to Appear at Senate Hearing on Credit Suisse Nazi Accounts

UBS Top Executives to Appear at Senate Hearing on Credit Suisse Nazi Accounts