The Biden administration moved Wednesday to throttle pollution from the nation’s cars and light trucks, imposing tailpipe emission limits so stringent they will compel automakers to rapidly boost sales of battery-electric and plug-in hybrid models.

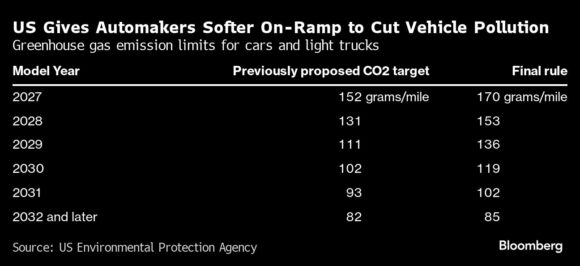

Though the near-term requirements were eased after pushback from automakers, the Environmental Protection Agency’s mandates would nevertheless require manufacturers to make a rapid shift toward zero-emission vehicles.

The rule delivers the “strongest-ever vehicle pollution” standards in US history, EPA Administrator Michael Regan proclaimed Wednesday, as he touted the measure inside the Washington, DC armory surrounded by electric vehicles. “These technology-neutral and performance-based standards give the auto industry the flexibility to choose the combination of pollution control technologies best suited for their customers.”

The measure represents one of the most sweeping — and visible — climate regulations advanced by President Joe Biden, who has made combating global warming a top priority. Biden’s other marquee climate policies — targeting planet-warming pollution from oil wells and power plants — have broad economic reach but do their work mostly out of the view of consumers. By contrast, the auto standards will influence decisions from Detroit to driveways across the US, ultimately affecting some of the biggest purchases typically made by American households.

Under EPA’s modeling of one scenario, automakers might seek to comply with the 2032 requirements by boosting battery-electric vehicles to 56% of total US sales, with the penetration for plug-in hybrids at 13% and conventional combustion-engine cars at 29%.

Under EPA’s modeling of one scenario, automakers might seek to comply with the 2032 requirements by boosting battery-electric vehicles to 56% of total US sales, with the penetration for plug-in hybrids at 13% and conventional combustion-engine cars at 29%.

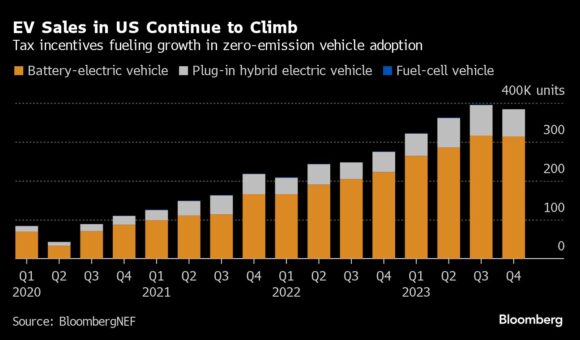

That broadly dovetails with earlier forecasts anticipating carmakers could comply by ensuring roughly two-thirds of their sales were battery-electric models, if plug-in hybrids were left out of the mix. Battery electrics now make up less than 8% of US sales, while plug-in hybrids represent barely 2%.

Automakers applauded concessions in the final rule, including the regulation’s bigger embrace of popular plug-in hybrids as a way to trim pollution. The measure also prolongs controversial credits for technologies that make cars more fuel efficient but don’t necessarily show up in tailpipe readings.

“These adjusted EV targets — still a stretch goal — should give the market and supply chains a chance to catch up,” said John Bozzella, president of the Alliance for Automotive Innovation. “It buys some time for more public charging to come online and the industrial incentives and policies of the Inflation Reduction Act to do their thing.”

Shares of General Motors Co., Ford Motor Co. and Stellantis NV all rose on the news. Tesla Inc. pared earlier gains.

Under the rule, tailpipe emissions of carbon dioxide are capped at 85 grams per mile in 2032 — down from 170 grams per mile for model year 2027. But much of those stringency gains would come after 2030. The requirements could nearly halve fleet average emissions over existing standards for 2026. The measure also sets limits on soot and smog-forming pollution, with mandates the administration said would deliver cleaner air for overburdened communities near major thoroughfares.

The standards are technology neutral, giving automakers options for complying with a mix of models, including hybrids, battery electrics and advanced gasoline vehicles.

The standards are technology neutral, giving automakers options for complying with a mix of models, including hybrids, battery electrics and advanced gasoline vehicles.

The Biden administration cast that as boon for consumer choice, with the regulation helping propel more electric options off assembly lines and on to dealer lots. “We are breaking the monopoly that one industry had on how we get from point A to point B” said White House adviser Ali Zaidi. “You no longer have to go to a gas station to make sure you can get to work or to school.”

Yet opponents — including Biden’s Republican challenger Donald Trump — have decried the measure as a defacto EV mandate, compelling automakers to focus on selling zero-emission vehicles at the expense of conventional, gasoline-powered cars. The regulation was also panned by the makers of liquid transportation fuels — including corn-based ethanol as well as petroleum, with the heads of the largest oil industry trade groups threatening to challenge it in court.

“The Biden administration has finalized a regulation that will unequivocally eliminate most new gas cars and traditional hybrids from the US market in less than a decade,” the presidents of the American Petroleum Institute and American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers said in a joint statement. “This regulation will make new gas-powered vehicles unavailable or prohibitively expensive for most Americans.”

Environmentalists had hoped the EPA would stick with its earlier, more aggressive proposal, which would require more up-front improvement. Even so, the final rule will keep an estimated 7.2 billion tons of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere between now and 2055, according to EPA estimates.

The transportation sector is the country’s largest source of planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions. Stifling that pollution is critical for the US to hit its Paris Agreement commitment to at least halve those releases by the end of the decade.

“This is the biggest climate action EPA has ever taken,” said Amanda Leland, executive director of the Environmental Defense Fund. “This is going to help save lives, it’s going to help kids and it’s going to give people a lot more choices.”

Once the requirements are fully phased in, American drivers would see an average $6,000 in savings from reduced fuel and maintenance costs over the life of a vehicle, EPA estimated. The limits also are projected to pare petroleum demand — with some 14 billion barrels of US oil imports shaved between now and 2055.

Toyota Motor Corp., which has been buoyed by rising hybrid sales, warned the standards would force “a precipitous shift.”

“Serious challenges around affordability, charging infrastructure and supply chain will need to be addressed before this mandate is realized,” the company said.

The National Automobile Dealers Association said the regulation outpaces consumer demand, adding the group is “highly skeptical that consumers will adopt EVs anywhere near the levels required.”

Even so, some environmental and consumer activists said the administration went too far to appease automakers. “The EPA caved to pressure” and “riddled the plan with loopholes,” said Dan Becker with the Center for Biological Diversity.

The measure is one of several rules governing vehicle pollution and efficiency. Automakers also must hit fuel economy requirements established by the Transportation Department, with EVs getting credit based on a just-updated Energy Department formula. The fuel economy and tailpipe standards are periodically updated by the federal government.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Cape Cod Faces Highest Snow Risk as New Coastal Storm Forms

Cape Cod Faces Highest Snow Risk as New Coastal Storm Forms  Why 2026 Is The Tipping Point for The Evolving Role of AI in Law and Claims

Why 2026 Is The Tipping Point for The Evolving Role of AI in Law and Claims  Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake

Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake  Hackers Hit Sensitive Targets in 37 Nations in Spying Plot

Hackers Hit Sensitive Targets in 37 Nations in Spying Plot