A few years before a 2023 cyberattack disrupted manufacturing at one of the largest US producers of disinfectants ahead of flu season, an audit warned of systemic cybersecurity flaws within the company’s production systems.

Among the shortcomings highlighted by the internal audit at Clorox Co., conducted in 2019 and 2020, were outdated computers, some of them running older Windows 98 and Windows XP operating systems that left them vulnerable to intrusion, according to three former employees who described the audit’s findings. The auditors urged Clorox to create a kind of digital perimeter around manufacturing plants, about 30 in total, located in the US and overseas, isolating them to reduce the disruption of an attack, according to the former employees and two current employees.

Instead, senior leaders at Clorox delayed improvements and cut back on recommended upgrades to cybersecurity defenses at the manufacturing plants, in part because they wanted to curb costs, according to the five people, who asked not to be identified to discuss internal company information. Most of the plants hadn’t received all of the recommended security upgrades by the time of the August 2023 breach, according to the current employees.

The vulnerabilities identified by the audit didn’t play a role in how the hackers got into Clorox’s systems, according to the company. Still, the three former employees and two current employees said having the upgrades recommended by the audit in place at the time of the attack could have helped to mitigate the fallout.

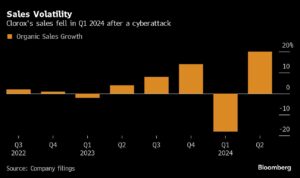

Following the attack, it took about three weeks for Clorox to get back to a level at which three quarters of its plants were producing products — and until Sept. 29, seven weeks after the attack, before all of its manufacturing sites had “resumed scheduled production,” according to the company. Meanwhile, stores ran out of cleaning supplies, and Clorox itself was missing out on hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of sales.

A Clorox spokesperson, Linda Mills, said it was “patently false” that Clorox delayed or cut back on recommended upgrades to digital defenses that made it vulnerable to breaches. She said the findings in the audit had no connection to the hack’s cause, severity or the company’s recovery. The ransomware incident didn’t infiltrate its production systems, which were disconnected as a precautionary measure, according to Clorox.

The hackers got into the company’s network via a social engineering attack that targeted a third-party IT help desk vendor. Clorox became aware of the intrusion within hours of it happening and immediately took steps to stop and remediate the damage, Mills said.

“The issues you raise did not cause or create any vulnerability to the cyberattack,” she said, in response to questions from Bloomberg. “Connecting the two is analogous to suggesting that not having a sprinkler system in one building is the reason why a completely different building experienced a fire.” She also disputed the current and former employees claim that having the recommended upgrades from the audit in place would have mitigated the fallout from the hack.

The issues raised by the audit had been “fully addressed or were already in the process of being addressed,” Mills said. Under Chief Executive Officer Linda Rendle, who took over in September 2020, the company has more than doubled its investment in cybersecurity in three years, Mills said. She declined to provide more detail about the company’s response to the audit or its investments in digital defenses.

The audit, and separately the breach itself, highlight the differences between technology used to manage data for such things as finance, human resources and email, and the software and hardware that operates industrial systems used in industries such as manufacturing, oil and gas and utilities. Those systems have become increasingly connected as businesses demand more remote access and real-time production data from manufacturing plants — or other industrial facilities — to drive decisions, according to Justin Turner, a director within the security and privacy practice at the consulting firm Protiviti. Turner wasn’t involved in responding to the Clorox hack.

But those connections — between what’s known as information technology (IT) systems and operational technology (OT) systems — also introduce security risks that must be considered, Turner said. The extent to which manufacturing facilities depend on a company’s IT network could potentially dictate how quickly production can resume following an attack, he said. Health and safety issues can also determine when factory production resumes, he said.

In 2021, for instance, hackers deployed ransomware against the IT network of Colonial Pipeline, the largest fuel pipeline in the US. The company was forced to shut down its pipeline for five days — causing fuel shortages along the US East Coast — to ensure the malware didn’t spread to the OT network, according to the company.

In 2021, for instance, hackers deployed ransomware against the IT network of Colonial Pipeline, the largest fuel pipeline in the US. The company was forced to shut down its pipeline for five days — causing fuel shortages along the US East Coast — to ensure the malware didn’t spread to the OT network, according to the company.

“It’s very hard to completely disconnect your OT and your IT,” said Luke Dembosky, partner and co-chair of data strategy and security at Debevoise & Plimpton, who advises companies on cyber risks but wasn’t involved in the Clorox breach response. He said it’s advantageous to keep connections between the two systems few and far between to make it harder for contagion to spread. “You try to keep it narrow.”

The audit of Clorox’s production systems focused on cybersecurity flaws in the OT network and recommended ways to protect and isolate it, according to the people familiar with it. However, Mills said, “The reason we took the time we did to reconnect our OT and IT environment was due to the size, scale and scope of our operations and had nothing to do with the state of security at the plant level prior to the attack.”

The company was cautious when reconnecting its manufacturing plants to a newly built IT environment, she said, adding, “We were dealing with a very sophisticated adversary that we needed to make sure was not somehow hiding in one of our remote locations, including the plants, just waiting for us to reconnect so that they could re-infect our IT network.”

Oakland, California-based Clorox makes not only disinfectant wipes and toilet-bowl cleaner but also a wide range of other products including Hidden Valley Ranch dressing, Burt’s Bees lip balm and Fresh Step cat litter.

The hack cost Clorox about $350 million in sales declines, and it is expected to incur costs of as much as $60 million related to the hack itself, according to Mills. Clorox’s sales rose in the latest quarter as it rebuilt store inventories across the country. The company said in February that it had recovered 86% of the distribution that it lost due to the breach. It still hasn’t fully restocked shelves for certain categories like cat litter and Glad bags, Chief Financial Officer Kevin Jacobsen said in a February interview.

This account is based on interviews with three current employees, four former employees and two vendors, all of whom requested anonymity to discuss sensitive information, in addition to information provided by Clorox.

The intrusion was first detected on Aug. 11, and it was made public on Aug. 14, when the company said it had detected “unauthorized activity” in its computer networks. The incident caused widespread disruption. The company told Bloomberg News after the breach that it was diverting newly idled factory staff to cleaning and training tasks and that it had to destroy expired products that it wasn’t able to ship.

Once in Clorox’s network, the intruders deployed ransomware, a type of malicious software that encrypts files held on computers and servers. Clorox cybersecurity personnel tried to eject the intruders from the network but couldn’t, so they began shutting down its computer systems in an attempt to stop the damage from spreading further, according to two people familiar with the matter. That action prevented the company’s manufacturing systems from being infiltrated, according to Mills.

Clorox declined to pay the hackers to unlock the compromised computers, according to a person close to the investigation. It’s not clear how much ransom was demanded.

The August 2023 incident wasn’t Clorox’s first security incident.

In a previously undisclosed incident in 2018, an employee in the company’s accounting department was tricked into paying about $500,000 in Clorox funds, according to three people familiar with the incident. An unidentified criminal pretended to be a contractor and duped the employee by email into making the payment to them electronically. With the help of the FBI, the company was later able to recover most of the funds, according to the people.

The FBI didn’t respond to a request for comment about the 2018 incident.

The Clorox Co. manufacturing facility in Forest Park, Georgia, U.S., on March 10, 2021. Photographer: Matt Odom/Bloomberg

Following the scamming incident, Clorox began more extensively training its employees to guard against common hacking methods, three of the people said. Mills acknowledged the incident but denied it led to more extensive cybersecurity training, saying the company had “consistently promoted practical and real-world training of employees against cyberattacks.”

But the company’s manufacturing plants nonetheless remained vulnerable, the three people said. The audit began as a routine evaluation by a small team at Clorox of the security at one plant, according to one of the people. Clorox later brought in a third-party auditor to carry out a larger assessment at multiple plants to get a better understanding of issues — both one-off and systemic — affecting the manufacturing environment, the person said.

The audit found that some production systems weren’t sufficiently protected by firewalls and security appliances that could isolate them from external networks and monitor and shut out potentially malicious activity, according to the three people.

Company bosses were at times reluctant to shut down manufacturing plants for cybersecurity upgrades, according to the people. That coincided with the first years of the pandemic, when Clorox struggled to meet demand for disinfecting wipes and was running its own facilities 24 hours a day to meet demand.

Clorox’s cyber defenses had other issues, complicated by two decades of acquisitions that created a patchwork of old and new machines that was difficult and costly to maintain and upgrade, according to the people. Clorox didn’t respond to a request for comment about its alleged reluctance to shut down plants and the alleged patchwork of machines.

Meanwhile, a half dozen or so cybersecurity specialists ended up leaving the company, partly due to frustrations over a perceived lack of investment in cybersecurity under Rendle’s tenure as CEO, said the people. Some of the departed employees hadn’t been replaced by the time the attack occurred last summer, two current employees said. That left the company short on expertise in areas such as threat and risk management and security engineering, they said.

Mills, the Clorox spokesperson, said the company had made “significant upgrades” to its cybersecurity infrastructure, including on vulnerability management, cloud security, mobile device security, threat detection, identity and access management. Claims that Clorox hadn’t replaced cybersecurity roles is inaccurate, she said, adding that the company had “redesigned our cybersecurity team to upgrade skill sets with stronger focus in engineering, architecture and risk management, and modernized our infrastructure.” The overall size of the company’s IT security team has increased over the last four years, she said, adding that Clorox has increased its third-party staffing as well.

In mid-2021, after the internal audit was completed, Clorox recruited a new chief information security officer, or CISO. But the company’s leadership merged the security job with another role, vice president of enterprise security and infrastructure, two former employees said. Some employees said that change had posed challenges for the incoming CISO, Amy Bogac, as she had to juggle what amounted to two high-pressure jobs rather than focusing solely on cybersecurity. Bogac didn’t respond to requests for comment. Mills said it was inaccurate to suggest Bogac’s dual roles compromised the company’s security focus or posture.

At the time of the hack, Clorox had been in the process of implementing a $500 million digital transformation, initially proposed by Rendle in 2021. But that effort was focused on upgrading the company’s enterprise resource planning system — software used to manage day-to-day business activities — and didn’t encompass cybersecurity upgrades for manufacturing facilities, according to three people familiar with the situation. Clorox didn’t respond to questions about the focus of the digital transformation.

Clorox declined to identify the hackers responsible. In October, Bloomberg News reported that the suspected perpetrator was a group known as Scattered Spider, the same gang tied to last year’s cyberattacks on MGM Resorts International and Caesars Entertainment Inc. The gang is known to specialize in targeting IT help desks, impersonating employees to obtain access to accounts.

In the intrusion at Clorox, the intruders impersonated employees and duped help desk assistants into resetting credentials to gain access to accounts, according to the two current employees. Once logged in, they gained broader access to the company’s systems, eventually compromising its Active Directory, a Microsoft service used to manage permissions, devices and users within a network, they said.

Social engineering attacks can happen regardless of a company’s cyber defenses, said Katie Moussouris, founder and chief executive officer of cybersecurity firm Luta Security. But she added, “Good cyber best practices will help in later detection, containment and recovery after any breach.”

Moussouris said creating strong limits on what privileged users can do inside company networks can mitigate the extent of the damage once a hacker has infiltrated. Such controls can restrict the ability of hackers to move freely within internal systems if they obtain passwords for privileged accounts through methods such as social engineering, she said.

In calls with investors, Rendle has remained upbeat. During a conference on Feb. 22, she indicated that the company was still trying to regain both its retail shelf space and lost customers. “The job is not done until we fully recovered households, we fully recovered distribution, we have all of our merchandising back,” she said. “We have the plans in the back half to do that and the investment to support it.”

In November, Clorox’s board of directors named Rendle as its chair starting in 2024, praising her handling of the cyberattack.

Around the same time, Bogac, the CISO, left the company after two and a half years in the role. A Clorox representative said in an internal memo, reviewed by Bloomberg News, that Bogac “was a champion of cybersecurity best practices externally and across the company.” Mills said Bogac’s departure didn’t occur because Clorox was hacked.

Clorox has since posted an advertisement recruiting for a chief information security and infrastructure officer. The successful candidate, the advertisement says, will need to “identify and protect against key threats.

Top photo: The Clorox Co. manufacturing facility in Forest Park, Georgia, U.S., on March 10, 2021. Photographer: Matt Odom/Bloomberg.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case  US Will Test Infant Formula to See If Botulism Is Wider Risk

US Will Test Infant Formula to See If Botulism Is Wider Risk  Portugal Rolls Out $2.9 Billion Aid as Deadly Flooding Spreads

Portugal Rolls Out $2.9 Billion Aid as Deadly Flooding Spreads  Cape Cod Faces Highest Snow Risk as New Coastal Storm Forms

Cape Cod Faces Highest Snow Risk as New Coastal Storm Forms