Trinity Public Utilities District’s power lines snake through the lower reaches of the Cascade Range, a rugged, remote and densely forested terrain in Northern California that has some of the highest wildfire risk in the country. But for several years, the company has been without insurance to protect it from such a threat.

Trinity’s equipment was blamed for causing a 2017 wildfire that destroyed 72 homes and three years later its insurer, a California public agency called the Special District Risk Management Authority, told the utility that it would no longer cover it for fires started by its electrical lines. Trinity could find no other takers.

The utility’s exposure comes as wildfires are already flaring up across the US West in what could be a dangerous and prolonged fire season.

“If a fire were to start now that involved one of our power lines, it would likely bankrupt the utility,” said Paul Hauser, general manager of the local government-owned utility that serves about 13,000 rural customers in Trinity County, 200 miles (322 kilometers) north of Sacramento. That’s because without insurance, a lawsuit could put the utility on the hook to pay for damages to private homes and businesses, which could easily top the utility’s annual revenue of about $16 million.

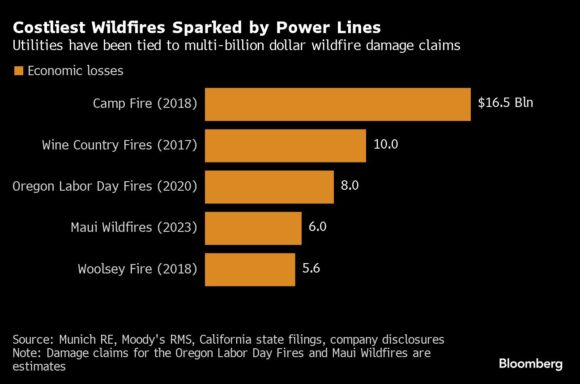

Western utilities and beyond are finding it prohibitively expensive, if not impossible, to insure against potential fire-related claims. The trouble comes after power companies from Hawaii to Texas have collectively faced tens of billions of dollars in damages from wind-driven wildfires linked to their equipment. The issue will become more pressing as climate change makes droughts more intense and frequent, heightening the chances of more destructive infernos.

“Wildfire risk is the number one issue for utilities,” said Michael Kolodner, the practice leader for the US power and renewables industry at Marsh & McLennan Companies Inc., a US insurance broker. “This is impacting every single utility in North America.”

“Wildfire risk is the number one issue for utilities,” said Michael Kolodner, the practice leader for the US power and renewables industry at Marsh & McLennan Companies Inc., a US insurance broker. “This is impacting every single utility in North America.”

The insurance companies set up by the utilities are now limiting how much coverage they will provide to power companies exposed to wildfire risk, leaving them at the whim of the commercial marketplace where premiums are rising.

Overall, commercial wildfire insurance rates have gone up as much as 30% this year with premiums also increasing the past several years, according to Marsh. Portland General Electric, based in Oregon, said their fire insurance premiums doubled.

The insurance challenges are now making it more expensive and difficult for some utilities to attract the capital required to harden their grids against climate risks and build out the infrastructure needed to meet President Joe Biden’s goal of a carbon-free grid by 2035.

“If utilities can’t get insurance or if the insurance is really expensive, it’s harder for them to construct new facilities they need to build like transmission lines and distribution lines,” said Michael Wara, an expert on utility wildfire risks who serves as director of the Climate and Energy Policy Program at Stanford University. The problem is akin to potential homeowner being unable to secure a mortgage to buy a house because they can’t get property insurance, Wara said.

Randy Howard, general manager of the Northern California Power Agency, which has 16 public power utility members including Trinity, says the lack of commercial insurance is making it hard for some his utilities to attract financing to build high-voltage transmission lines that the state wants to connect to renewable energy projects.

“It’s impacting investors’ willingness to invest in these projects that we need to build,” Howard said.

The utility industry is openly discussing the need to set up a federal program that could provide a type of insurance backstop for smaller power companies that have limited financial resources. Such a fund would cover claims for utilities that have agreed to meet certain fire risk reduction standards. The fund could be modeled after one set by California after PG&E Corp. filed for bankruptcy in 2019 in the wake of starting some of the worst wildfires in state history.

As it stands now, utilities have become the “insurer of last resort” when it comes to damage claims from wildfires tied to their equipment, said Emily Fisher, general counsel at the Edison Electric Institute, an investor-owned utility trade group. The industry has become difficult to insure because there isn’t a limit to their potential wildfire liabilities, Fisher added.

Power companies also need to spend billions of dollars to make their infrastructure less prone to start fires, funding fixes such as installing weather monitoring equipment, burying power lines and replacing old poles. “It’s not a sustainable regime,” Fisher said.

Warren Buffett agrees. In the billionaire investor’s recent annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway Inc. shareholders, Buffett said he’s reconsidering his utility investments due to the heightened wildfire risk in the US West. Berkshire’s PacifiCorp utility, which operates in six Western states, was found liable in 2023 for destruction caused by the 2020 Labor Day fires in Oregon. PacifiCorp is appealing the decision. The utility faces wildfire claims estimated to be as much as $8 billion, according to a regulatory filing.

“We are basically in the position of being the insurer of last resort because we cannot get enough commercial insurance,” PacifiCorp Chief Executive Officer Cindy Crane said at a S&P power markets conference in April. “We had a pretty good volume of wildfire insurance and we blew through that.”

PacifiCorp has obtained wildfire insurance, but its premiums have increased more than 400% from 2019 through 2022, a spokeswoman said.

Utilities also have been turning to state governments for help. PacifiCorp backed legislation passed earlier this year in Utah that sets up a catastrophic fire insurance fund for utilities and caps non-economic damage claims arising from utility-linked fires.

In 2019, California set up a $21 billion wildfire insurance fund to prevent additional investor-owned utility bankruptcies after PG&E was driven into Chapter 11 for sparking fires in 2017 and 2018 that killed more than 100 people and destroyed thousands of homes.

California investor-owned utilities, which contributed to half of the fund, can qualify for the coverage if they meet certain fire safety standards. The fund covers claims above $1 billion, with the utilities having to find insurance up to that amount.

Even that has proven to be difficult. PG&E decided to self-insure against wildfire risk in 2023 after the utility saw its cost for commercial wildfire insurance as a percentage of coverage jump from 4.6% in 2015 to nearly 80% in 2022, when the utility paid about $746 million for $940 million in coverage, according to regulatory filings.

PG&E estimates its self-insurance program, which works by putting aside money collected from bills for possible claims, will save customers up to $1.8 billion over the next four years compared to commercial insurance coverage. Southern California Edison has also opted to self-insure after seeing its commercial coverage rates skyrocket.

However, publicly-owned, government-run utilities like Trinity aren’t part of California’s wildfire insurance fund, leaving them entirely exposed. The state’s legal regime holds utilities responsible for damage claims from fires started by their equipment — whether they were negligent or not. (While the liability standard is looser in other states, it hasn’t gotten utilities off the hook in places like Oregon).

Trinity Public Utilities District is stuck in a problematic cycle where it can’t do the work required to make its own property safer from fire. The utility wants to widen the clearing around its existing lines on federal land from 20 feet to up to 130 feet to reduce fire risk, but it cannot start that work without a new federal permit. And it cannot get a new permit unless it has wildfire insurance.

“We are kind of the poster child for this issue,” Hauser, the general manager, said. “No one will insure us.”

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings

FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings  Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case  Elon Musk Alone Can’t Explain Tesla’s Owner Exodus

Elon Musk Alone Can’t Explain Tesla’s Owner Exodus  LA County Told to Pause $4B in Abuse Payouts as DA Probes Fraud Claims

LA County Told to Pause $4B in Abuse Payouts as DA Probes Fraud Claims