The black-and-white message flickering across computer screens sparked panic at Knights of Old, a 158-year-old U.K. delivery company: “If you’re reading this, it means the internal infrastructure of your company is fully or partially dead.”

Knights’ network for managing trucks was down. So was the system for booking payments. From 2,000 miles away, a criminal, Russia-linked hacking gang known as Akira had sabotaged the computers at Knights of Old and two related trucking companies. To force negotiations, the crooks in June 2023 had deployed malicious software that encrypted Knights’ files and then threatened to publish online its confidential internal data. Paying a ransom would get the company a decryption key that could be used to unlock the compromised computers and servers, Akira said.

“For now, let’s keep all the tears and resentment to ourselves and try to build a constructive dialogue,” the gang wrote in a note on Knights’ infected machines. “We’re fully aware of what damage we caused by locking your internal sources.”

In 2023 ransomware attacks rose 70% from a year earlier, to 4,611, according to the SANS Institute, a cybersecurity research and training organization. Since March 2023, Akira alone has victimized more than 350 organizations and extorted an estimated $42 million, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation and a Bloomberg analysis found. (The gang, which maintains a website, didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

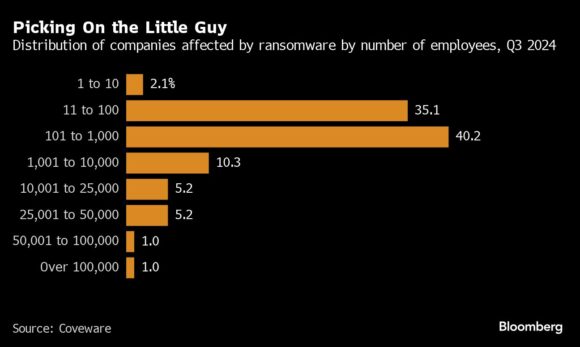

Akira has had some high-profile targets, such as Nissan Motor Co., Stanford University and Yamaha Motor Co. But cybersecurity researchers have found that about 80% of its victims are small and medium-size organizations, most in North America and Europe. “No business can ignore this threat, no matter how big or small,” says Paul Abbott, 58, Knights’ co-owner.

According to digital insurance company Embroker, most smaller businesses set their policy limits for cybersecurity damages at $1 million, close to the level at Knights. That money could potentially be used to pay a ransom and help rebuild infected computers. But it’s often nowhere near enough. The median ransom payment soared to $6.5 million in 2023, from $335,000 the year before, insurance broker Marsh & McLennan Cos. found.

Will Thomas, a cybersecurity expert who’s closely tracked Akira’s attacks, says the group identifies its targets by scanning the internet for servers that are operating outdated software, then opportunistically breaches them. “What they do is not particularly complicated or sophisticated,” Thomas says. “But they are very successful, and they are ruthless.”

In 1865, William Knight started making deliveries in a horse and cart he drove through an English village called Old, about 80 miles north of London. Hence his company, now based in nearby Kettering, would come to be known as Knights of Old. Abbott, who grew up in the area, knew the Knight family, and at age 20 he joined Knights of Old. He worked first as a traffic manager, helping to route the trucks and supporting drivers and customers. Abbott steadily climbed the ranks, and around 2007 he and two business partners, who didn’t respond to requests for comment, became directors and then co-owners. They later joined Knights of Old with two other delivery companies—Nelson Distribution Ltd. and Steve Porter Transport Ltd.—under the name KNP Group.

By the time of the hack, KNP had almost £100 million ($126 million) in annual revenue, 900 employees, seven depots and 400 trucks. Knights was the biggest and best known of the three companies, its trucks bearing an image of an armored knight and a vivid color scheme of bright blue with huge yellow letters spelling out the motto “Service With Honour.” Among its customers were publishing giants Penguin Random House LLC and Hachette Book Group, which relied on its fleet to distribute millions of books for Amazon.com Inc. and other retailers. In early 2023, KNP leased a 140,000-square-foot warehouse in Luton, near London, as part of an expansion effort.

Having experienced computer failures in the past, Abbott and his colleagues had already established an alternative way of working. They could revert to writing out paper tickets and job sheets for each delivery and use their mobile phones and Gmail.

Abbott had thought the company was secure. Just a month before the intrusion, he’d arranged a £1 million cyberattack policy through the British insurer Aviva Plc, which declined to comment. Managers had also trained staff on cybersecurity awareness and were paying about £60,000 annually to a contractor that provided support. But following the attack, he says, the contractor—whom he declines to name—provided little help and “didn’t have a clue” what to do.

After the initial attack, Aviva arranged for a team of experts from security company Solace Cyber to help. The following morning it began to digitally clean all electronic devices—computers, laptops, even photocopiers—that were connected to the company’s network. Paul Cashmore, Solace’s managing director and co-founder, says the breach had inflicted devastating damage. He recalled navigating Knights’ employees through a roller coaster of emotions. “First there was the shock. Then it’s realization. Then it’s dealing with the impact,” he says. Solace is currently working on about two major ransomware incidents every week, Cashmore says, and the pace shows no sign of slowing.

Knights consulted US-based company Coveware Inc., which specializes in negotiating with ransomware hackers, Abbott says. The company, which declined to comment, told him that, based on KNP’s size and revenue, the Akira gang would likely expect a payment in Bitcoin worth $2.7 million to $5.3 million. Law enforcement agencies generally advise against paying ransoms because it incentivizes further attacks. Sending cryptocurrency to the gangs could also violate sanctions that are in place against some of the criminals involved.

Abbott said he and his partners decided not to negotiate with Akira or pay the gang anything, because there could be no guarantee the data could be fully recovered even with the decryption key. In response the hackers followed through on their threat, publishing more than 10,000 internal documents online—mostly employee payroll files, invoices and other financial information.

The company tried to rebuild its computers. Within a few days, Knights’ technicians had set up a new transport management system and recovered an old backup of the warehouse software. But the financial management databases couldn’t be immediately recovered, because hackers had destroyed another backup that was supposed to be stored securely elsewhere.

Facing cash-flow pressures, KNP sought a loan. Abbott says the bank would provide it only if the company could supply the missing financial records and performance reports. Still waiting on a payout from the insurance company, the co-owners tried to sell the company. A European businessman came close to buying. But, because of the missing financial records, the buyer insisted that the three partners personally guarantee the state of the company’s finances. They’d be putting their houses and savings on the line. The partners balked, according to Abbott. “My wife would never have let me do that, regardless of how confident we were in the business,” he says.

On Sept. 25, 2023, KNP Group entered administration, the British equivalent of bankruptcy. In Kettering, Abbott announced the news to his employees, some of whom he’d worked with for decades. Another company bought one of KNP’s subsidiaries, Nelson Distribution, saving about 170 jobs. But the rest of KNP’s 700 or so employees, the majority of them from Knights of Old, lost their livelihood. Jeff Maslin, who drove trucks for Knights, says drivers are still owed weeks’ worth of wages. “I know people who lost their house, lost their car and ended up divorced,” he says.

KNP later determined that Akira had gained access to the company’s systems using a technique called “brute forcing,” which can employ software that makes thousands or millions of guesses to discover a staffer’s password. Abbott says more sophisticated security monitoring software might have helped detect the intrusion. “If you haven’t got that, get it,” he advises other companies.

Earlier this year, administrators began the process of selling Knights’ headquarters, along with KNP’s other assets. The fleet of trucks, mostly leased, has been returned. The insurer eventually paid out on the £1 million policy, but it didn’t cover Knights’ losses in administration.

Abbott, now working as a consultant for other logistics companies, recently bought a single truck and plans to use it to start over. “I’ve had to rebuild my life,” he says. “I’ve lost everything.”

Gallagher works in Bloomberg’s Edinburgh bureau and covers cybersecurity.

Top photo: Abbott Photographer: Ryan Gallagher/Bloomberg.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Why 2026 Is The Tipping Point for The Evolving Role of AI in Law and Claims

Why 2026 Is The Tipping Point for The Evolving Role of AI in Law and Claims  These Five Technologies Increase The Risk of Cyber Claims

These Five Technologies Increase The Risk of Cyber Claims  Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake

Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake  Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo

Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo