Eleven property owners whose homes were flooded after a city of Brownsville official closed a flood gate may proceed with their claims against the city because of a statute that waives governmental immunity for damages caused by motor-driven equipment, the Texas Supreme Court ruled.

The high court on Friday reversed a decision by the 13th District Court of Appeals that dismissed the homeowners’ claims. The plaintiffs should have been allowed to present evidence that city stormwater manager Jose Figueroa’s operation of the North Laredo Gate caused their damages, the opinion says.

“The parties do not dispute that the North Laredo Gate has a motor,” the decision says. “Nor do they dispute that Figueroa, a city employee, closed it.”

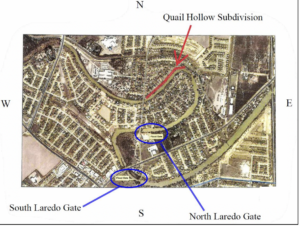

A normally dry channel, called a resaca, passes through the Quail Hollow neighborhood in Brownsville. It was once a river bed that carried the flow of the nearby Rio Grande.

In August 2015 a severe rainstorm caused water to start running through the resaca. Initially, the water flowed in the usual direction from west to east, but after hours of rainfall the flow reversed.

Figueroa, concerned that the backward flow would cause flooding in Quail Hollow, closed the North Laredo gate immediately downstream. The parties dispute whether he did so manually or used a motor-driven actuator. About an hour later, water behind the closed flood gate backed up into 11 Quail Hollow homes.

The homeowners contend that Figueroa should have known that the backward flow was only temporary. They filed a lawsuit against the city alleging their homes would have remained dry if the flood gate had been left open.

Generally, municipalities are immune from tort liability because of a concept known as sovereign, or governmental, immunity. The Texas Legislature, however, passed a law that allows lawsuits against governmental bodies for damages caused by the operation of motor-driven equipment.

Parties that sue governmental bodies must show that immunity is waived. A Cameron County judge decided that the Quail Hollow homeowners had met that burden, but the Court of Appeals, in a split decision, found that the homeowners were alleging the “non-use” of the flood gate had caused the flooding, so there was no immunity waiver under the statute, which is Section 101.021(1)(A).

The Supreme Court disagreed. The court said because the North Larado Gate is normally left in an open position, it was the act of closing the gate that arguably caused flood damage to the 11 homes.

“Closing the gate put it to its intended purpose: blocking water.,” the opinion says.

The high court remanded the case to the 107th District Court in Cameron County. The decision does not give the plaintiffs a green light to proceed to trial, however. The Supreme Court said other facts, for example, whether Figueroa opened the flood gate by hand or used its motor, may impact the trial court’s decision on whether immunity has been waived.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case  Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud

Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud  Portugal Rolls Out $2.9 Billion Aid as Deadly Flooding Spreads

Portugal Rolls Out $2.9 Billion Aid as Deadly Flooding Spreads  FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings

FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings