Spring dumped so much rain on the U.S. that most of the country is drought-free for the first time in decades. But in parched Florida and Georgia, wildfires have destroyed hundreds of thousands of acres of forests and pastureland.

There’s no relief in immediate sight. “We are buckled up for a very long and very hot wildfire season,” said Adam Putnam, the commissioner of agriculture in Florida, the largest producer of orange juice behind Brazil.

The culprit is a high-pressure ridge that has stubbornly hovered since late last year over the region, pushing storms away. Interestingly enough, it’s the same atmospheric system that can steer hurricanes into the southeastern U.S., and if it doesn’t spin far out over the Atlantic this summer, it’ll be in position to catch a tempest and fling it toward land.

But for now, all that’s certain is that the system has put much of Florida and Georgia in stark contrast to the rest of the continental U.S.: This April was the second wettest in the 123-year-old record, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information in Asheville, North Carolina.

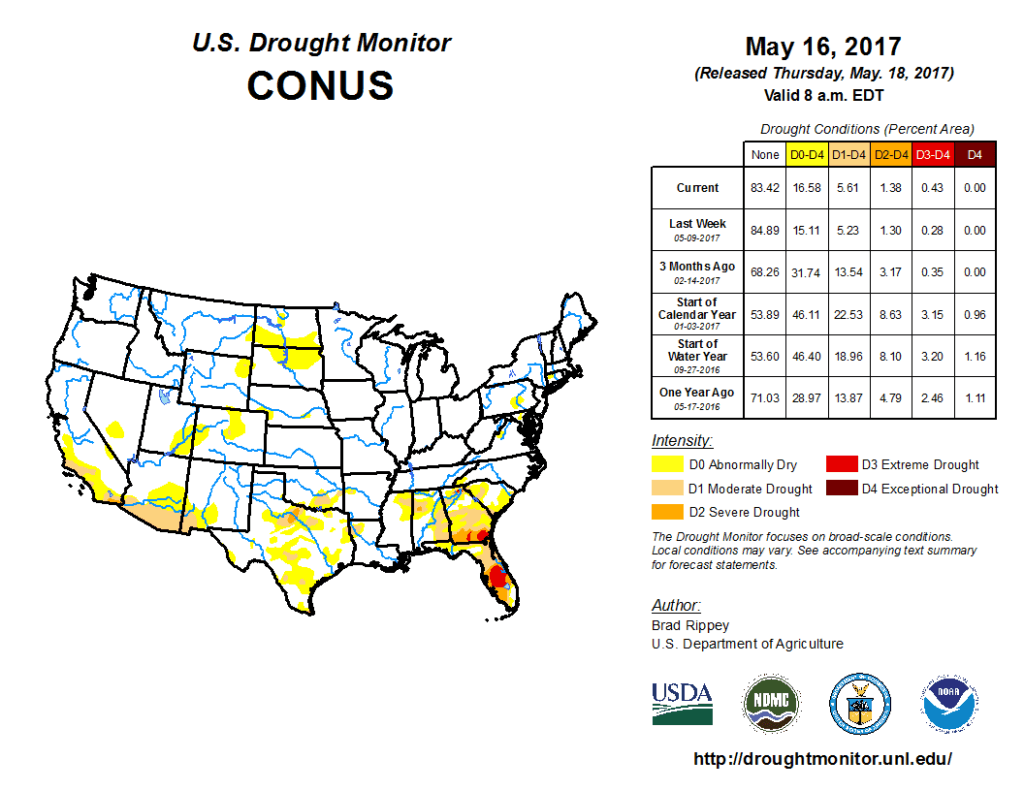

Even California is for the most part out of a punishing years-long drought. By the measure of the Palmer Drought Severity Index, the U.S. probably hasn’t been this drought free since June 1993, said Brad Rippey, a meteorologist with the Department of Agriculture and a member of the U.S. Drought Monitor team in Lincoln, Nebraska.

Georgia, though, is 88 percent abnormally dry or in drought, just under double what it was a year ago, according to the monitor. In Florida it’s almost 82 percent, up from 6.47 percent last year.

The wildfires, the most intense in Florida since 2011, have burned at least 30 homes and at one point closed down parts of Interstate 75. The West Mims fire in southeast Georgia that started in April is raging over 150,000 acres of the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge.

While flames haven’t reached citrus groves, “certainly the trees are stressed by the drought,” Putnam said. Most Florida groves are irrigated, protecting them from drought. The commissioner said it’s too early to put a price on the damage to livestock and crops.

Last winter’s weak La Nina could have contributed to the region’s woes because the south often gets dryer when the equatorial Pacific cools, said Stephen Baxter, a seasonal forecaster at the U.S. Climate Prediction Center in College Park, Maryland. But summer usually delivers rainfall. “We are waiting for that seasonal shift,” Rippey said.

Last year, Hurricane Matthew drenched the coast from Florida to North Carolina with flood-spawning rains. The U.S. hasn’t been hit by a major storm, Category 3 or higher, since 2005.

There’s no way to forecast at this point whether another big one is in store. “But there is some statistical information that says when Florida is in drought, Florida has a much higher chance of being hit,” said Dan Kottlowski, a meteorologist at AccuWeather Inc. in State College, Pennsylvania.

He’s watching that high-pressure system, still nosing in off the ocean to cover much of the state. The Atlantic hurricane season starts June 1.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings

FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings  Hackers Hit Sensitive Targets in 37 Nations in Spying Plot

Hackers Hit Sensitive Targets in 37 Nations in Spying Plot  Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake

Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake  Cape Cod Faces Highest Snow Risk as New Coastal Storm Forms

Cape Cod Faces Highest Snow Risk as New Coastal Storm Forms