BOISE, Idaho — Atmospheric nuclear weapons testing exposed more states and more people to radiation fallout and resulting cancers and other diseases than the federal government currently recognizes, Western governors said.

The Western Governors’ Association on Friday sent letters to the U.S. Senate and U.S. House urging passage of proposed changes to a law involving “downwinders.”

The U.S. between 1945 and 1992 conducted more than 1,000 nuclear weapons tests, nearly 200 in the atmosphere. Most were conducted in Western states or islands in the Pacific Ocean.

The changes to the 1990 Radiation Exposure Compensation Act would add all of Nevada, Arizona and Utah, and include for the first time downwinders in Colorado, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico and the island territory of Guam.

The changes would also include increasing the maximum payment to $150,000 for someone filing a claim. Compensation currently ranges from lump sums of $100,000 for uranium workers to $50,000 for those who lived downwind of the Nevada Test Site.

The new legislation called the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act Amendments of 2019 would also include those who lived downwind of the 1945 Trinity Test in New Mexico’s Tularosa Basin.

“We encourage you to expeditiously consider and approve this important legislation, which acknowledges that nuclear weapons production and testing has had much broader impacts than currently recognized by statute,” the governors wrote in letters to each chamber signed by Oregon Democratic Gov. Kate Brown and North Dakota Republican Gov. Doug Burgum.

Tona Henderson is the director of Idaho Downwinders, which for years has sought the inclusion of Idaho in the compensation program.

She said 14 of her 38 family members in the Emmett area in southwestern Idaho have died of cancer, the youngest at 15, and many others have survived that and other diseases. She has battled cancer and other health issues.

During the nuclear testing, farmers would go out to their fields on summer mornings to find them covered with dust carried on the wind from the nuclear blasts, she said. The dust occurred so often, she said, it picked up the name “summer frost.”

“I don’t know why we weren’t included,” said Henderson, who was an infant growing up on her parents’ dairy farm during the tail end of the atmospheric testing in the early 1960s. “Other than the government didn’t want to admit that they did something wrong.”

The Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium in New Mexico is another group seeking recognition as having been adversely affected by nuclear testing.

“We don’t wonder if we’re going to get cancer, we wonder when,” said Tina Cordova, a cancer survivor and co-founder of the Tularosa consortium.

The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act was first passed in 1990 as an alternative to costly litigation to ensure the federal government met its financial responsibilities to workers who became sick as a result of the radiation hazards of their jobs.

The proposed legislation on the Senate side was introduced earlier this year by U.S. Republican Sen. Mike Crapo of Idaho. Crapo for years has sought the inclusion of Idaho as a downwind state.

Besides downwinders, the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act also includes money for workers made sick during uranium ore mining and milling activities that took place in 11 states in the Western U.S.

Downwinders should receive equal compensation as offered those workers, Henderson said.

“Energy workers knew what they were signing up for,” she said. “We didn’t know what was happening to us.”

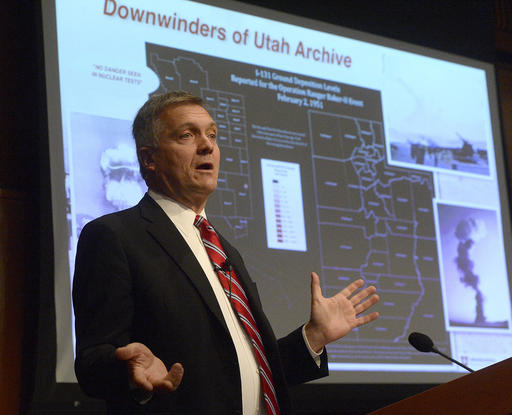

About the photo: In this Oct. 3, 2016 photo, former Utah Congressman Jim Matheson, an advocate for compensation for the downwind population in Utah affected by cancer speaks at the launch event for “Downwinders of Utah Archive” at the J. Willard Marriott Libray at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. (Al Hartmann /The Salt Lake Tribune via AP)

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo

Canceled FEMA Review Council Vote Leaves Flood Insurance Reforms in Limbo  Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake

Berkshire Utility Presses Wildfire Appeal With Billions at Stake  Portugal Rolls Out $2.9 Billion Aid as Deadly Flooding Spreads

Portugal Rolls Out $2.9 Billion Aid as Deadly Flooding Spreads  China Bans Hidden Car Door Handles in World-First Safety Policy

China Bans Hidden Car Door Handles in World-First Safety Policy