46 percent of claims are being overpaid by an average of $19,000

In his book, The Flaw of Averages, author Sam Savage explores how the widely used statistical concept of “averages” can wreak havoc on our forecasting and decision making. He explains the law’s weakness by pointing out, “Plans based on average conditions are wrong on average,” and describes common, avoidable mistakes in assessing risk in sectors as diverse as healthcare, accounting and climate change. In our business we frequently see operational rules of thumb based on such averages.

A recent example of how this plays out in the real world involved a top claims service provider for a top 5 insurance carrier. The service provider told the carrier that their data analysis showed the 250 most expensive items on a contents claim represented 80 percent of the Replacement Cost Value (RCV) of all personal property in the household.

As a result of this analysis, the insurance carrier used this data to create what they thought was a streamlined process for handling large contents losses. Adjusters would ask the insured to itemize their top 250 most expensive items, appraise those items and then “gross up” the total amount from 80 percent (i.e., dividing the amount by .8). This amount becomes the basis of settlement discussions for large losses.

Upon hearing this from the carrier, we thought this sounded oversimplified so we dug into our data warehouse of settled contents claims. We analyzed several thousand total losses to determine the average number of line items that equates to 80 percent of RCV. We found that it takes, on average, the most valuable 430 contents line items to cover 80 percent of RCV—not 250 as originally posited.

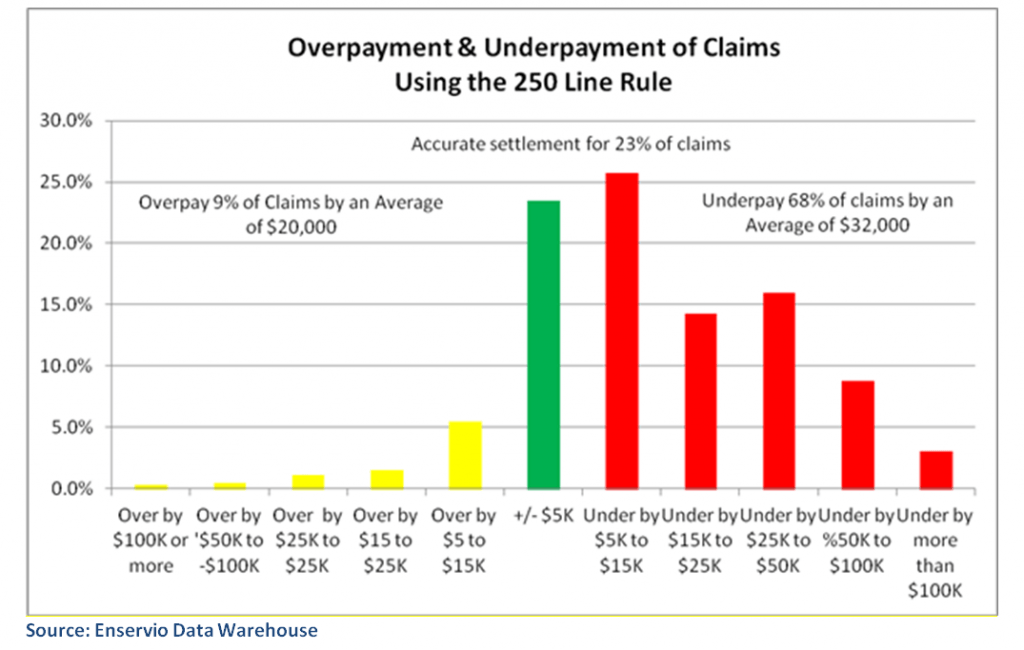

In other words, our analysis shows the “rule of thumb” is off by 72 percent. (Editor’s Note: 430 lines is 72 percent greater than 250 lines.) But it gets even worse. As the next chart shows, the 250 lines rule of thumb causes the carrier to underpay as much as 68 percent of the RCV for its contents claims, with an average of $32,000 underpayment per claim. Viewed in this context, it becomes immediately clear that this represents a pretty significant bad faith risk for the carrier.

What is obvious from such an evaluation is that the insurance carrier simply didn’t have enough data to make an accurate assessment.

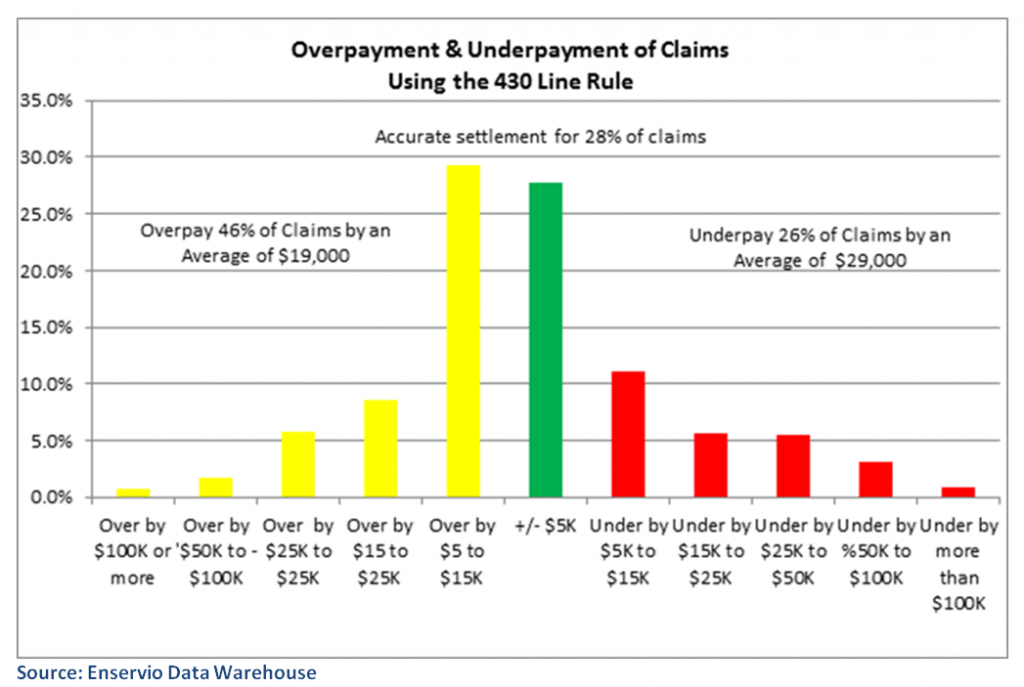

Tapping into a data warehouse of millions of contents claim lines (i.e., line items on a claim sheet) we conducted further analysis to look at the distribution of claim outcomes using a new “430 Line Rule” based on our initial revelation. The results were equally illuminating. In fact, the problem moved from underpayment to overpayment. Our chart below shows 46 percent of claims are being overpaid by an average of $19,000.

Of course, it might seem reasonable for an insurance claim manager to assert that making overpayments at least eliminates bad-faith risk. However, he would also have to acknowledge that the loss ratio would balloon as a result. With the 430-lines rule 46 percent of claims are being overpaid by an average of $19,000

The truth is, these are two pretty bad choices. But since the insurance industry has not historically had much analytics on contents coverage, insurers have long used such inaccurate rules of thumb.

Take the longstanding rule for single-family properties that sets the Coverage C limit as a percentage of Coverage A. Most carriers use this technique, which says the cost of rebuilding a home is correlated to the value of personal property inside the household. This rule says that a home with a retired empty nester couple will require the same Coverage C as an identical home, in the same neighborhood, with a married couple with three teenagers. The common wisdom holds that this is the best practice since claims are settled faster, and carriers reduce their loss-adjusting expenses. (See also, related article, Using Big Data To Improve Homeowners Insurance Products.)

However, fast settlements which reduce loss-adjustment expenses are not replacements for good adjusting and underwriting practices, and certainly do not excuse gross errors in loss payments.

The fact is insurers have viable alternatives to the crude rule-of-thumb approach in settling large contents claims. There are analytical products emerging that deliver useful estimates of contents that accurately reflect the specifics of the insured household, and their property.

Of course, the best estimating process begins with an on-site inventory, assembled by a professional specializing in such claims. Given the dollar errors inherent in the rule-of-thumbapproach, the cost of this service is quite justified for large contents claims. Experience demonstrates that such an approach dramatically improves accuracy, and reduces settlement time.

And that’s a combination that results in satisfied customers.

About the Authors

James Fini is Vice President, Research and Development and Founder of Enservio, a provider of software and services for P&C carriers to price policies correctly and settle contents claims with more accuracy. He may be reached at jfini@enservio.com or www.enservio.com.

Frank Cregg, Enservio’s Director of Business Analytics, has more than 20 years of experience in product development and pricing in personal lines insurance. He is a graduate of Harvard College with an MBA from the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud

Charges Dropped Against ‘Poster Boy’ Contractor Accused of Insurance Fraud  China Bans Hidden Car Door Handles in World-First Safety Policy

China Bans Hidden Car Door Handles in World-First Safety Policy  LA County Told to Pause $4B in Abuse Payouts as DA Probes Fraud Claims

LA County Told to Pause $4B in Abuse Payouts as DA Probes Fraud Claims  FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings

FM Using AI to Elevate Claims to Deliver More Than Just Cost Savings