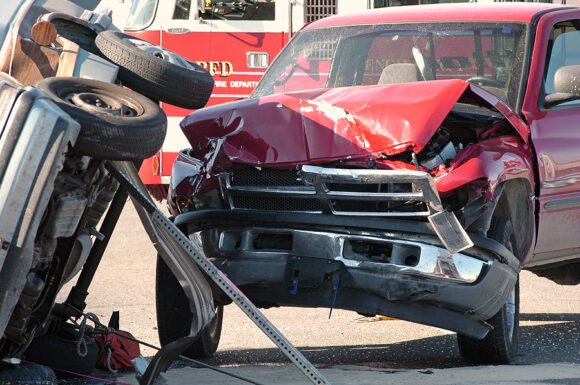

When and whether a vehicle involved in a collision is considered to be “totaled” for first-party insurance purposes is an issue of great angst and confusion for most consumers. We hear horror stories about older, functioning automobiles being “totaled” simply because the frame is bent or other seemingly minor and hidden damage occurs. Even insurance professionals can get turned around navigating the maze of rules and regulations regarding the act of “totaling” a vehicle under a policy. But it needn’t be all that complicated. This article will hopefully help take the guess-work out of when a car can be “totaled.”

Typically, cars are considered to be “totaled” when the cost to repair the vehicle is higher than the actual cash value (ACV) of the vehicle. Practically speaking, however, it is not always practical to repair a vehicle, even if the cost of repair is less than its ACV. A vehicle worth $4,000 requiring $3,000 in repairs might be considered “totaled” by an insurer even though the cost of repair is less than its value before the accident. Insurance companies will typically consider such a vehicle to be a total loss, even though the repairs are only 75 percent of ACV.

Typically, cars are considered to be “totaled” when the cost to repair the vehicle is higher than the actual cash value (ACV) of the vehicle. Practically speaking, however, it is not always practical to repair a vehicle, even if the cost of repair is less than its ACV. A vehicle worth $4,000 requiring $3,000 in repairs might be considered “totaled” by an insurer even though the cost of repair is less than its value before the accident. Insurance companies will typically consider such a vehicle to be a total loss, even though the repairs are only 75 percent of ACV.

While the procedure varies slightly from state to state, the insurance company will typically take ownership of the totaled vehicle (known as “salvage”) and may obtain a “salvage title” for the vehicle. After it pays it’s insured the pre-loss ACV of the vehicle and forwards the certificate of ownership, the license plates and a required fee to the Department of Motor Vehicle (DMV), the DMV then issues a Salvage Certificate for the vehicle. In some cases, the vehicle is repaired, re-registered with the DMV, and then classified as a “revived salvage” or “salvaged” vehicle. Of course, if the insured wants to keep the “totaled” vehicle, the insurance company will deduct the value of the salvage from the claim payment.

The criteria for deciding when a car is a total loss and when it can be repaired vary from insurance company to insurance company and might even be dictated and controlled by state statute or regulation. Further complicating the issue is the fact that insurance companies do not all use the same sources for determining the value of a vehicle. The threshold used by your insurance company to make this determination can be discovered by calling your insurance agent. Insurance professionals, on the other hand, have to be familiar with these rules, criteria, and thresholds in all 50 states.

In determining whether a vehicle is totaled, insurance companies will calculate the total loss ratio (cost of repairs/actual cash value) and then compare this ratio to limits set either internally within the company and/or regulated and established by state law. It is also sometimes referred to simply as the damage ratio. Some states dictate how high this damage ratio needs to be in order to be able to declare a vehicle a “total loss” and be eligible for a salvage title or certificate. This is referred to as the Total Loss Threshold (TLT). In order to total a vehicle, the total loss ratio must exceed the established percentage. If the TLT is not dictated by the state, an insurance company will usually default to something known as the Total Loss Formula (TLF) which is:

Cost of Repair + Salvage Value > Actual Cash Value

If the sum of the first two quantities is greater than the ACV, the car can be declared a total loss. As an example, a damaged 2002 Toyota Echo with 185,000 miles in good condition has an ACV of approximately $2,800. Total repair costs are estimated at $2,000, for a damage ratio of 72 percent. This car would be considered a total loss in Arkansas, where the TLT is 70 percent, but not in Florida where the TLT is 80 percent. In Illinois, the TLF would be used and, if the salvage were worth $700, the car would not be totaled ($2,000 + $700 < $2,800). Of course, states utilizing the TLF rely on and defer to the judgment and opinions of licensed appraisers. Individual state laws provide the following with regard to the TLT:

| Alabama | 75% | Montana | TLF |

| Alaska | TLF | Nebraska | 75% |

| Arizona | TLF | Nevada | 65% |

| Arkansas | 70% | New Hampshire | 75% |

| California | TLF | New Jersey | TLF |

| Colorado | 100% | New Mexico | TLF |

| Connecticut | TLF | New York | 75% |

| Delaware | TLF | North Carolina | 75% |

| Florida | 80% | North Dakota | 75% |

| Georgia | TLF | Ohio | TLF |

| Hawaii | TLF | Oklahoma | 60% |

| Idaho | TLF | Oregon | 80% |

| Illinois | TLF | Pennsylvania | TLF |

| Indiana | 70% | Rhode Island | TLF |

| Iowa | 50% | South Carolina | 75% |

| Kansas | 75% | South Dakota | TLF |

| Kentucky | 75% | Tennessee | 75% |

| Louisiana | 75% | Texas | 100% |

| Maine | TLF | Utah | TLF |

| Maryland | 75% | Vermont | TLF |

| Massachusetts | TLF | Virginia | 75% |

| Michigan | 75% | Washington | TLF |

| Minnesota | 70% | West Virginia | 75% |

| Mississippi | TLF | Wisconsin | 70% |

| Missouri | 80% | Wyoming | 75% |

States frequently dictate this TLT as part of legislating salvage titles. As an example, in Wisconsin, § 342.065(1)(c) reads as follows:

(c) If the interest of an owner in a vehicle that is titled in this state is not transferred upon payment of an insurance claim that, including any deductible amounts, exceeds 70% of the fair market value of the vehicle, any insurer of the vehicle shall, within 30 days of payment of the insurance claim, notify the department in writing of the claim payment and that the vehicle meets the statutory definition of a salvage vehicle, in the manner and form prescribed by the department.

Many states have exceptions to these rules for older vehicles which tend to complicate the issue. Typical policy language regarding total losses is as follows:

We will pay the cost to physically repair the auto or any of its parts up to the actual cash value of the auto or any of its parts at the time of the collision. The most we will pay will be either the actual cash value of the auto or the cost to physically repair the auto, whichever is less. We will, at our option, repair the auto, repair or replace any of its parts, or declare the auto a total loss. If, the repair of a damaged part will impair the operational safety of the auto, we will replace the part.

Understanding the procedure behind declaring a vehicle a total loss isn’t always a prerequisite for successful subrogation. But there are occasions when the third-party tortfeasor and its liability carrier or attorney will question the amount of damages you are looking to subrogate. In such instances, a working knowledge of this area of insurance becomes indispensable.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says

Credit Suisse Nazi Probe Reveals Fresh SS Ties, Senator Says  Cape Cod Faces Highest Snow Risk as New Coastal Storm Forms

Cape Cod Faces Highest Snow Risk as New Coastal Storm Forms  Hackers Hit Sensitive Targets in 37 Nations in Spying Plot

Hackers Hit Sensitive Targets in 37 Nations in Spying Plot  Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case

Navigators Can’t Parse ‘Additional Insured’ Policy Wording in Georgia Explosion Case